The Fifth Day of the Fifth Month

“Girls’ Day” (the third day of the third month) is Hina Matsuri, the Doll Festival, so it belongs on these pages. “Boys’ Day” (the fifth day of the fifth month) has a more complicated status and does not require a doll display. The most important festive item is a banner or windsock in the shape of a carp (koi nobori), which is flown from a pole near the home; one fish is raised for each boy child. The carp is equated with virility because of the strength with which it swims upstream. The day is also associated with the iris flower, whose sword-shaped leaves invite little boys to duels and mock battles. Names for the festival include Tango no sekku (“horse festival,” as the fifth month is the month of the horse), Shobu no sekku (Iris festival), or just Gogatsu (5th month).

However, many dolls have been made to be purchased and displayed on the day: soldiers and great generals, legendary rulers and spiritual guides, and boy heroes whose outrageous activities invite some of the most inventive doll designs. Certain animals are also significant: tigers used to be displayed as a reminder of Japan’s relationship with Korea, and a white horse to evoke the Emperor. The most important element of the “doll” display is miniature armor or a helmet, and during the Edo period a samurai family might display real heirloom armor. A doll representing an armed soldier or lord is a Musha ningyo. In the second half of the 19th century, when power was centralized around the emperor, the doll display was a significant way of promoting a sense of national identity, not only through the shared historical legacy but also through stories about child heroes who, though as young among men as Japan was young among nations, exercised power wisely and generously. Dolls representing contemporary generals and soldiers were made in the early part of the 20th century, too, including images of the Emperor himself in military dress. This is a day for celebrating martial arts and martial glory–or it used to be.

In 1948, the holiday was rededicated by the Japanese government to all children–not just boys–as Kodomo no hi.In principle, the family flies a carp banner for each member of the younger generation, girl or boy. “Gogatsu” (fifth month) dolls are still popular, though now they are usually made to represent little boys, inspiring tenderness rather than awe.

Musha ningyo: how does one “read” the details of a “samurai doll”?

- Usually a pale face indicates youth and/or aristocratic rank. Flesh-colored skin indicates exposure to the elements, therefore age, an active life, or both. Sometimes the white faces are enhanced by the super-aristocratic “sky-brows,” dark smudges high on the forehead over the actual eyebrows; the imperial couple of the hina dolls usually have this kind of face, but some Musha ningyo also have it, in particular the Empress Jingu and her son, Ojin.

- Men had their hair shaved in different patterns during the course of their lives; the shaved area might be colored blue on a doll. An adult man had all the hair on the top of his head, from the hairline back, shaved off, and the side hair worn long and tied back, sometimes in a folded tail that sticks straight up or is arranged forward on the top of his head.. A young man would have a shaved patch but a forelock left on, which might be tied back over it. A woman (there are some woman warriors among the Musha ningyo!) has long hair and no shaved patch. A monk or priest would have all or most of the head completely shaven. Certain dolls usually are shown with facial hair (Takenoshi, the white-haired minister of Empress Jingu, Benkei, and Kato Kiyomasa) but more usually the face of a high-ranking hero is clean-shaven.

- An important warrior doll–a general, shogun, or emperor–might be wearing an eboshi, the tall brimless hat with a “dent” in the front, gold or black. Or he might wear an elaborate battle helmet with flaps to cover his neck (kabuto). The Japanese dollmakers refined the art of combining miniature metalwork with lacquered paper and silk lacings to create realistic and beautiful armor–breastplate, shoulder protectors, and five panels of leg protection.However, certain dolls–Jimmu Tenno and Shoki–wear long robes in a style associated with ancient China, indicating their legendary status.

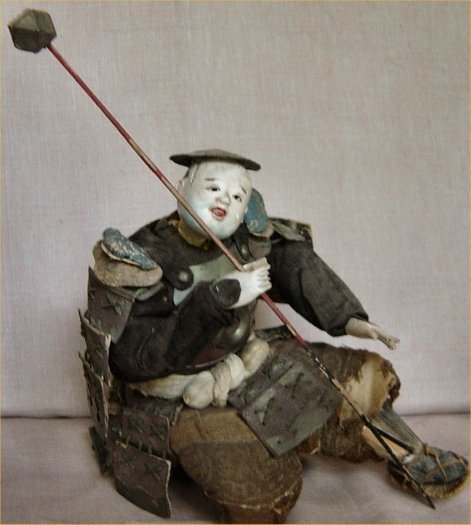

- A general or emperor would be seated, usually on a wooden stool. He might hold a battle fan; he would certainly wear a sword and should have a second knife as well in his belt, and he might have bow and a quiver of arrows as well. He might have a scabbard or other accessories of “tiger skin,” indicating dominion over Korea, land of tigers. An emperor might be attended by a famous general or minister historically associated with him, and also by a kneeling bannerman holding his personal flag. The bannerman wears a bowl-shaped helmet (jingasa) and armor; he often has a rather comical expression.

Whom do the dolls represent?

Most of the warrior dolls represent a specific historical or legendary person. The exception would be dolls that belong to the “supporting cast” of bannerman, footsoldier, etc. However, the depiction is normally very idealized, so that it may not be easy to decide which famous youthful general is represented. In the late 19th century a style called iki-ningyo came into fashion, which depicted people in a more realistic way, and this produced some beautiful portrait-like Musha ningyo. I list here a selection of characters, divided into three groups: legendary figures from the mythical history of the Emperors, historical figures who are linked to the history of the military Shogunate, and boy heroes. However, there is a great deal of overlap; the 12th-century general Minamoto no Yoshitsune was certainly historical, but there are many legends about him and his friend Benkei; moreover, some of the stories focus on his boyhood adventures.

Legendary figures

- Jimmu Tenno

- First emperor of Japan, grandson of the sun goddess Amaterasu, ancestor of all Japanese emperors. He would have lived around 600 BC. Depiction: Solemn pale but flesh-colored face, straight black beard, Chinese-style robes and boots. He stands, holding a pole on which a bird, a golden kite, perches. He wears around his neck the Imperial Treasure, a mirror and a necklace of jewels. Often paired with Shoki.

- Shoki

- “The Demon-Queller.” Chinese hero, a student or general who committed suicide but later appeared to the Chinese emperor and was able to protect him from demons. Depiction: Angry-looking ruddy face, very bushy black hair, beard, and eyebrows. He wears Chinese-style clothes and boots, often golden or of rich brocades, and wears a hat with flaps sticking out to the side. His belt buckle is a demon’s face, indicating that he has devoured the beast. He stands holding a straight sword in one hand and spreads the other hand out to ward off demons.

- White Horse

- The white horse is ridden by the emperor. It is supposedly the offspring of a mare and a dragon! When shown as a figure by itself, it has saddle and stirrups.

- Jingu Kogo (Empress Jingu)

- The wife, then widow, of Emperor Chuai, then regent for their son Ojin. When her husband died (possibly around the year 200), this empress went fishing to get an omen as to whether she should continue his plans to conquer Korea. The omens were auspicious. She led the Japanese military on sea and land, although she was pregnant. She gave birth near the battlefield only after the Korean army was defeated. Depiction: Always has a white face and almost always “skybrows”. Hair is tied back and she wears red clothing, sometimes over armor, and a gold eboshi hat. Usually shown with Takenouchi (and the infant Ojin), sometimes with a soldier or bannerman as well. She may be fishing with a spear turned into a fishing-pole, or she may be seated or standing after having given birth to Ojin. I also have a doll in which she is mounted on a white horse.

- Takenouchi no Sukune

- Jingu’s elderly councillor and general, who also served her son. Depiction: An old man, usually smiling, with flesh-colored face and white hair and beard, in battle armor. Often shown kneeling, with one knee on the ground, holding the baby Ojin.

- Ojin or Hachiman

- Jingu’s son, deified after his death as the god of war. Depiction: Appears as a baby in tableaux with Jingu and Takenouchi. Also appears as an adult emperor, with white face, usually clean-shaven, seated holding a war fan.

Historical figures

- Yoshitsune (Ushiwakamaru)

- Minamoto no Yoshitsune was the great young general of the late-12th-century wars of the Genji and Heike (Minamoto and Taira) clans. These wars heralded the end of the period when the emperor dominated Japanese culture; Yoshitsune’s brother Yoritomo is accounted the first shogun. Yoshitune led his party to military victory but was condemned as a traitor by Yoritomo, who wanted to consolidate his own power, and was eventually hunted down and died (by his own hand). Many legends arose around Yoshitsune’s life: that he was raised by a bird-demon, the Tengu king, who trained him in agility; the fidelity of his wife; his adventures with his companion the warrior monk Benkei. There is a story that he escaped to China where he became Genghis Khan. Plays were written about these stories, books were illustrated, and of course dolls were made. Depiction: As a seated general doll, Yoshitsune wears an elaborate helmet. He may look quite fierce, but he usually has a youthful face, very white (though he may have blue “5 o’clock shadow” too), and sometimes with “skybrows.” In post-WWII warrior dolls, a little boy in warrior gear with a big helmet is usually identified as Yoshitsune. Ushiwakimaru (Yoshitsune as a young boy) is a white-faced boy, usually with his hair styled with two loops on top. He may be depicted with a flute and/or a veil over his head, looking very young and girlish. Alternatively, he may be shown brandishing a flag with a rising sun (see Benkei below for details on these presentations of Ushiwakamaru, which are related to the incident at the Gojo Bridge.).

- Benkei

- The probably completely legendary companion and servant of Yoshitsune. He was said to be a very large man, almost a giant in size and strength. He was a Buddhist monk, and he represents the character, already obsolete in the Edo period, of a priest who is also a warrior or bandit. He dominates some important Kabuki plays: Funa Benkei, in which his prayers avert a storm, and Kanjincho, in which Benkei improvises an escape for himself and Yoshitsune across a watched border. Kanjincho is the basis for Akira Kurosawa’s film They who step on the Tiger’s Tail. Funa Benkei is not a common doll-subject, but Kanjincho is quite common (see below). Depiction: Benkei always has a flesh-colored face and is usually bald or nearly bald, with a handlebar moustache, though in some cases he may be clean-shaven with Kabuki makeup. He is often dressed in armor but rarely wears a helmet; he may however have a white scarf wound around his head. He may be shown carrying a gigantic bell, which he stole from/gave to a monastery according to a legend. Two special Yoshitsune-Benkei scenes:

- Gojo Bridge: Benkei first encountered Yoshitsune ( as the boy Ushiwakamaru) on the Gojo Bridge in Kyoto, the old capital; this episode is also a popular woodblock print subject. Benkei was trying to collect the weapons of 1,000 men crossing a bridge (by challenging them to duels), with the idea of forging himself a perfect sword. Ushiwakamaru was the first man able to evade him. Other versions of the story say that it was Ushiwakamaru who was bothering travellers, and Benkei who took charge of the younger man on the bridge! He may be shown in armor, alone or in a scene with Ushiwakamaru, defending the bridge with a pack of terrible weapons on his back. When the scene includes Ushiwakamaru, the boy, in geta, flies up onto the bridge railing and beans Benkei with his fan. Benkei is sometimes portrayed in post-WWII dolls as a little boy dressed as a monk (often with a scarf over his head) with the pack of weapons on his back.

- Kanjincho, This is the encounter at a border crossing, where Yoshitsune, fleeing his brother, is disguised as Benkei’s servant; Benkei himself pretends to be a priest collecting donations to restore a temple. Benkei wears the Kabuki play costume, a black surcoat over a plaid garment and white pants, with white pompoms down the front, and a tiny black priest’s hat. He should be holding a scroll and a nice accessory is the scroll case. Yoshitsune wears a broad straw hat and a poor man’s cloak to hide his identity, but his boyish white face makes it evident. The third figure is the border lord who allows himself to be fooled into letting the heroes escape; he wears a tall hat and elegant clothing.

- Hideyoshi

- In 1590-98, Toyotomi Hideyoshi was involved in the wars which led to the establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate in Edo. He was a great general but did not himself become Shogun. He was of peasant birth, but developed refined tastes (e.g., for the tea ceremony). His emblem was the gourd. Depiction: He is usually shown seated in a kneeling posture (not on a stool) in full armor, or standing. He may wear a helmet which has a metal sunburst fanning out from the back, or a Chinese cap with side flaps. His face is plump (though the historical man was thin) and his expression somewhat fierce.

- Kato Kiyomasa

- Hideyoshi’s general, from the same town and also of humble birth. He was a formidable fighter and leader, and helped with the invasion of Korea. He seems to have been a cruel man who loved only battle. Depiction: He wears a distinctive conical helmet with antlers on it. He may be standing by Hideyoshi or he may be portrayed by himself, thrusting a spear at a tiger which represents Korea.

- Chushingura or the 47 Ronin

- This is not a common doll subject but I own an example, so I include it. In 1701, an incident occurred in the Shogun’s palace: Lord Kira insulted newcomer Lord Asano, and the younger man drew his sword. Since this gesture was illegal, Asano had to kill himself (seppuku) and his family had to forgo vengeance. His men dispersed and became ronin, masterless samurai; however, nearly two years later, 47 of them reunited, having spent the intervening time plotting a raid on Kira. They slew Kira, offered his head at the grave of Asano, and then were themselves condemned to commit seppuku. Almost immediately this story of extreme loyalty (and conflict between legal and personal justice) became well-known and soon it was made into a Kabuki play. Several films of this story have been made, entitled either Chushingura or The 47 Ronin. Depiction: I have only seen a few dolls relating to this story, usually portraying Oishi, the leader of the 47. He is recognizable by his mon or emblem of two interlocking comma shapes on a contrasting ground.

Boy Heroes

- Momotaro

- The “Peach Boy.” This is a children’s story about a boy found in a large peach by a childless old couple. He grows into a valiant youth who, with the help of three animal companions, slays the local ogre and retrieves his treasure for his parents. This story became particularly important as an emblem of modern Japanese nationhood in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when Japan seemed to be “growing up” very fast. Depiction: Momotaro is depicted as a child or adolescent boy. His face may be white or flesh-colored. In most representations from the first half of the 20th century, he has a banner reading “Japan #1.” He usually wears armor and may hold a peach, or his banner may have a peach on it. He may be accompanied by one or more of his animal friends (a dog, a monkey, and a pheasant); in the most elaborate presentations, the animal is depicted as a child or warrior with some indication of the animal nature, such as an animal mask or garment motif. Momotaro may also be depicted enjoying the treasure (a cart full of “jewels” including a branch of coral), or triumphing over the demon (who looks a lot like a Western devil).

- Kintaro (Kintoki)

- A heroically strong little boy. He grew up to be the companion of an 11th-century warrior, Minamoto no Yorimitsu. Kintaro supposedly was born in the mountains; his mother was a wild woman (a legendary type of being). In woodblocks, the mother and son are often shown, contrasting her white skin with his red skin. Depiction: He is usually shown as a very muscular, ruddy little boy, with minimal clothing and a triangular black lacquer hat. He may be catching or riding a carp, riding on a bear, or teaching smaller animals to wrestle.

- Urashima Taro

- “The fisher-lad of Urashima.” This is another children’s tale. Because of his kindness to a sea-turtle, the young fisherman goes to live in the palace of the ruler of the seas (sometimes presented as a dragon king), and marries the princess. After a while, however, he wants to visit his family; he is given a box which he must not open; he goes home to Urashima and finds that hundreds of years have passed. He opens the box and instantly ages and dies. Depiction: A young man in clothing that evokes a peasant of fishermaan on a turtle or with a turtle. Sometimes he is shown holding the box. In two-figure scenes he appears with the sea princess, whose garments are designed so as to seem to float.

- Ushiwakamaru

- See above under “Yoshitsune.”