Plath and the Periodic Table

I’m teaching The Bell Jar this week in my “Desperate Domesticity” class on the American 1950s. And what strikes me this time around is English major Esther Greenwood’s adventures in physics and chemistry (they culminate Chapter 3). Call it Plath’s periodic fable of women and STEM in the era of “rocket girls” and rocket bras.

A straight-A student, Esther found her first day of physics class rather ghastly as soon as her professor went to the blackboard: Then he started talking about let A equal acceleration and let T equal time and suddenly he was scribbling letters and numbers and equals signs all over the blackboard and my mind went dead. Wallace Stevens’s enigmatic line Let be be finale of seem in “The Emperor of Ice Cream” was infinitely easier. And so, apparently, was James Joyce’s notoriously difficult Finnegans Wake, the topic Esther would pursue in her honors thesis. Esther studied the STEM hieroglyphics of scorpion-lettered formulas. She mastered the 400-page textbook her professor had produced to explain physics to college girls–a terrifying tome composed of diagrams and more formulas.

Esther aced that physics class, showing that women had more to offer the atomic age than nuclear families. But she would rather launch a book than join the Space Age rocket girls. And she wants a vibrant life in which she can shoot off in all directions myself, like the colored arrows from a Fourth of July rocket.

So Esther devised a plan to just audit the chemistry class. The same professor used the periodic table of elements in which all the perfectly good words like gold and silver and cobalt and aluminum were shortened to ugly abbreviations with different decimal numbers after them. The materiality of these elements was, for her, the materiality of language.

So Esther devised a plan to just audit the chemistry class. The same professor used the periodic table of elements in which all the perfectly good words like gold and silver and cobalt and aluminum were shortened to ugly abbreviations with different decimal numbers after them. The materiality of these elements was, for her, the materiality of language.

She wrote villanelles and sonnets during her chemistry lectures, foregoing milliliters and milligrams for the metrical and rhythmic formulas of poetry–mirroring Plath’s own apprenticeship to poetic form. If Esther Greenwood felt STEMrolled by the physical sciences, Plath knew that poetry also had essential elements.

I’ll close with a periodic table of poetry that Plath used in some of her college publications: Shakespearean sonnet structure. Here’s the first quatrain of her 1954 poem “Doom of Exiles,” which demonstrates how the strictures of poetic form offered Plath a looser confinement than scientific tables. (I’ve italicized the stressed syllables.) Each unit is a poetic foot, and each line conforms to the 5-foot pattern. But individual words can stretch across these units, and all lines need not have 5 beats. Even formal poets are free to break the rules:

Now we, | retur | ning from | the vaul | ted domes

Of our | colos | sal sleep, | come home | to find

A tall | metro | polis | of cat | acombs

Erec | ted down | the gang | ways of | our mind.

If nuclear physics splits the atom, formal poetry fits individual words to patterns. See if you can re-join the words I’ve split here.

–MB

SOURCES:

Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar. 1963. New York: HarperPerennial, 2006.

Sylvia Plath, Collected Poems. New York: 1981. HarperPerennial, 1992.

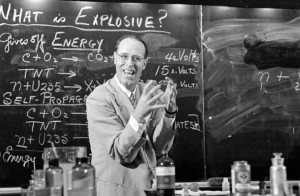

Photograph of Hubert Alyea from LIFE.com

Comments are currently closed.