Stone Stories: Louise Erdrich and Geologic Time

A stone is a thought that the earth develops over inhuman time. — Louise Erdrich

A stone is a thought that the earth develops over inhuman time. — Louise Erdrich

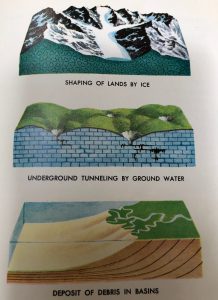

The first stories I remember were children’s stories my mother read to me, and Bible stories I heard in church. Sometime during elementary school, I found the bedrock story of my childhood–Jerome Wyckoff’s book Geology: Our Changing Earth through the Ages. Its illustrated “spiral of time” stretched across two pages. This was a different kind of story. I stared at the illustrations that plunged  beneath Earth’s surface, poring over cross sections of fault lines, volcanoes, and water.

beneath Earth’s surface, poring over cross sections of fault lines, volcanoes, and water.

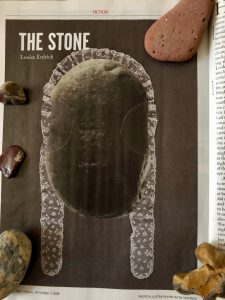

Last week I read Louise Erdrich’s story “The Stone,”a new kind of bedrock story. Noticing a basalt stone in the woods, the central character keeps it to herself and carries it home: Water had scoured two symmetrical hollows into the stone, giving it an owlish look, or a blind look, or, anyway, some quality that was oddly attractive. The girl abides with her stone as she ages–the story’s central (and centering) relationship. Its nearness and its ineffable gravity afford her self-sufficiency. This stone story reroutes the coming-of-age plot, moving beyond familial and romantic relationships. More than a material or a record, the basalt stone in Erdrich’s story is an actant. As the story expands into geologic time, the stone’s agency exceeds the dimensions of biological narratives. Commenting on her story, Erdrich asks: But who is to say that the stones aren’t using us to assert themselves? To transform themselves?

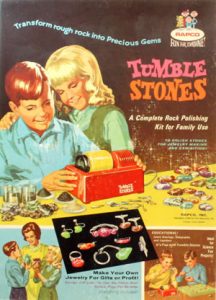

Rock plotting opens new seams in stories about ourselves, our families, our place in the world. Santa gave me a metal detector instead of Barbie dolls one year, followed by a Tumble Stones rock polishing kit. My own rolling stones ground away under my

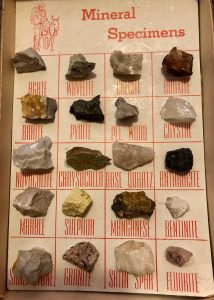

Rock plotting opens new seams in stories about ourselves, our families, our place in the world. Santa gave me a metal detector instead of Barbie dolls one year, followed by a Tumble Stones rock polishing kit. My own rolling stones ground away under my  bed for weeks on end. I dreamed of being a lapidary. (I missed the message on the box that rock polishing was for boys.) Years later Dad revealed that my Tumble Stones kept him awake at night, but he said nothing at the time. Mom gave me a flatware organizer so I could change its kitchen categories to Igneous, Sedimentary, and Metamorphic. Rock solid acts of love. My rock collection and geologic time took me outside the gender scripts of my own time. I have carried these rocks into new habitations in Tennessee, Illinois, and Florida. They have carried me into books, museums, and mountains.

bed for weeks on end. I dreamed of being a lapidary. (I missed the message on the box that rock polishing was for boys.) Years later Dad revealed that my Tumble Stones kept him awake at night, but he said nothing at the time. Mom gave me a flatware organizer so I could change its kitchen categories to Igneous, Sedimentary, and Metamorphic. Rock solid acts of love. My rock collection and geologic time took me outside the gender scripts of my own time. I have carried these rocks into new habitations in Tennessee, Illinois, and Florida. They have carried me into books, museums, and mountains.

A stone is, in its own way, a living thing, not a biological being but one with a history far beyond our capacity to understand or even imagine.

I finish reading Erdrich’s story late in the evening. I cross the room and pick up a small mica-faced stone I’d found in Grandma’s yard in North Carolina. As a child I saw its glint of silver in the gravel and picked it up. I stared into a mirror-like surface reflecting something further than I could see. I place this stone by my bed, sleeping more soundly than I have in many days. What I dream lies too deep to retrieve. – MB

SOURCES:

Louise Erdrich, “The Stone” in The New Yorker, Sept. 9, 2019. Quotes from Erdrich’s story and comments are in italics.

“Louise Erdrich on the Power of Stones,” interviewed by Deborah Treisman for The New Yorker. Sept. 2, 2019.

Ruth Van Beek, Photo Illustration for “The Stone”

Jerome Wyckoff, Geology: Our Changing Earth through the Ages. Golden Press. 1967.

My rock collection

https://rocktumbler.com/blog/rapco-tumble-stones-rock-tumbler/

Comments are currently closed.