This lesson plan unit is designed for MIDDLE SCHOOL/JUNIOR HIGH students in PHYSICAL SCIENCE classes and any SOCIAL STUDIES classes.

SUBTOPIC:

Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Thompson

OBJECTIVES:

The students will:

- understand the historic and cultural context of the foundations of the United States of America

- appreciate the application of practical knowledge into home conveniences

- identify the political and scientific contributions of Thompson, a.k.a. Count Rumford

- understand the clear, concise ideas expressed by Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence

- understand the basic electrostatic charge

- understand why there was a movement during the 18th century toward acceptance of higher education

- understand the economic reasons for acquiring a college degree

- learn where these universities are located and be able to trace the most direct route on a US Map

Background Information

Patterned Nature: Beneficial Ruler of Science and Society

The 18th century is often associated with the Age of Enlightenment, characterized by the work of Sir Isaac Newton. Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin drew upon the Enlightenment premise that “viewed science as a God given instrument for rationalizing human institutions on behalf of individual liberty and social progress.” “Reason” and “Nature” were their slogans. Science was the supreme example of reason in action, yielding useful knowledge. Nature, in their view, was the atomistic world of invisible particles of matter, moving inexorably in accordance with wisely ordained laws, a world epitomized in Newton’s mathematical model of the solar system. Thus nature was a perfect symbol for those who viewed society as a collection of individuals seeking their own enlightened self-interest in a divinely ordained “system of natural liberty,” as Adam Smith called it. Out of the competition of ideas and opinions truth would emerge.

In essence, the age of Franklin, Jefferson and Thompson can be characterized by the idea that nature (social and physical) was seen as orderly and machine-like. If one will “tinker” with this machinery, then socially useful and practical applications will arise for the benefit of human-kind. The foundation of the principles are reflected in the US Constitution and the Bill of Rights. In this philosophy, one has a world in which society and science work hand in hand for the liberty and betterment of humankind, within a “natural” world.

“There is nothing that can better deserve our patronage than the promotion of science and literature. Knowledge is in every country the surest basis of public happiness.”

– George Washington

Address to Congress

8 January, 1790

ACTIVITY #1:

Jefferson’s Inventiveness: The Mechanical Advantage of the “Dumb Waiter”

1-2 class periods

PROCEDURE:

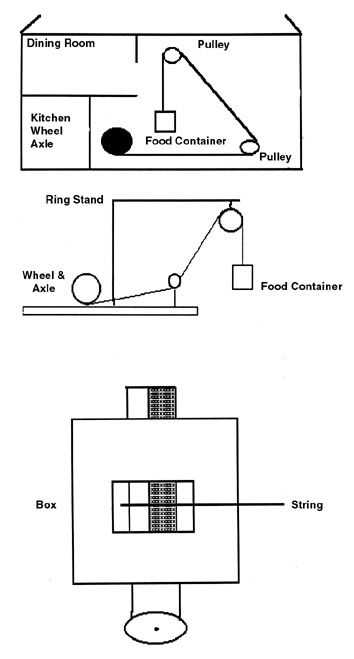

- Examine the illustration given on the following page of the dumb waiter Jefferson had built at Monticello. The food storage box would carry the contents into the dining room 12′ overhead by turning the handle 24 complete turns. The handle moved one foot with each turn. What is the ideal mechanical advantage of the dumb waiter?

- Optional: Test the mechanical advantage of the dumb waiter. (See diagrams on the next page.) The wheel and axle may be constructed by cutting the “wheel” from cardboard and gluing it to a dowel stick (axle) which may be mounted inside a box. Measure the force exerted on the wheel with a spring scale and compare it to the weight moved. The actual mechanical advantage involves the friction of the mechanism and uses the equation:

Mechanical Advantage = Force of the resistance

Force of the effort

The theoretical or ideal mechanical advantage does not take friction into account and is always greater than the actual mechanical advantage.

- Identify the ways friction can be reduced on the mechanism and implement each of them to determine their effect of the actual and theoretical mechanical advantage. List the results in the table below.

Suggestions include:

- modification of the pulley arrangement (See page 91B)

- modification of the wheel and axle, i.e. increase or decrease the diameter of both the “wheel” and “axle.”

- Determine the actual mechanical advantage of the model and compare it to the theoretical mechanical advantage, i.e. measure the force exerted on the wheel with a spring scale compared to the weight moved.

*Hint: The actual mechanical advantage involves the friction of the mechanism and uses the equation:

Mechanical Advantage = Force of the resistanceForce of the effort

The theoretical M.A. does not consider friction and is always greater than the actual mechanical advantage.

- Identify the ways friction can be reduced on the mechanism and implement each of them to determine their effect of the actual and theoretical mechanical advantage. List the results in the table below.

Original Model Theoretical M.A. ____Trial Data Actual M.A. ____

1 Factors to reduce friction Effect on M.A.

2 i.e., Lubricate pulleys

3

4

5

- Determine the efficiency of both the original model and the mechanism with the friction reduced.

Hints: The efficiency of a machine is a comparison of the work put into a machine, to work that is given back. The efficiency is never 100% due to the friction that is involved in the machine that cannot be totally removed.

Equation: Efficiency = work out = weight x distance moved

work in = effort x distance

“Work out” is measured by the force needed to lift the weight directly and the distance it is moved. “Work in” is measured by the force applied to the wheel and the distance over which the wheel moves.

Work = Force x Distance

ACTIVITY #2:

Declaration of Independence

1-2 class period

MATERIALS:

COPY OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE FOR EACH GROUP

PROCEDURE:

- Divide students into 5 or 6 groups depending on how you wish to discuss the Declaration.

Group I: Why Are the Colonies Fighting?Group II: Why Are Governments Established?Group III: What Do People Have The Right To Do If A Government Does Not Carry Out Its Duties?

Group IV: What Did the King Do to the Colonists?

Group V: Why are the Colonies Now Free?

Group I: Why was the Declaration Written?

Group II: Statement of Basic Human Rights.

Group III: Government Must Safeguard Human Rights.

Group IV: Abuses of Human Rights by the King.

Group V: Colonial Efforts to Avoid Separation.

Group VI: The Colonies Declare Independence.

- Each group will explain and discuss with the class how his/her part of the Declaration of Independence refers to what is “natural”.

- Encourage groups to use audio-visual aids to further their case for the colonies who separated from Great Britain. Show a precise flow of reasons for separation.

- Encourage groups to use audio-visual aids to demonstrate how Mr. Jefferson, in clear, concise language, states the ideals of American government, and to search for scientific principles in the Declaration.

ACTIVITY #3:

Get Charged Up

1-2 class period

MATERIALS:

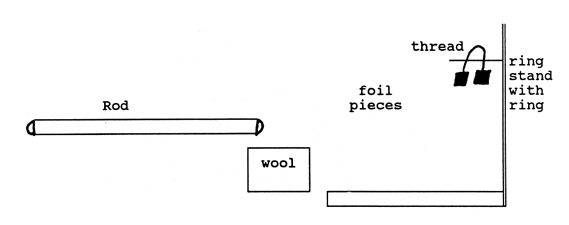

3 OR 4 BALLOONS, 15 PIECES OF WOOL CLOTH, 15 PLASTIC RODS, 10 ALUMINUM FOIL COVERED DRINKING STRAWS, SPOOL OF THREAD, 15 RING STANDS WITH RINGS

Background information for Activity

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) was an American author, statesman, and scientist who experimented with electricity. Adapting the preceding activity can reflect a link to his historical scientific experiments, by substituting a glass rod for the plastic rod and a piece of buckskin for the piece of wool.

PROCEDURE:

- In preparation, complete the following steps:

- Cut foil covered straws into 2 cm pieces and thread into 25 cm lengths.

- Rub wool on inflated balloons to put on the wall as anticipatory set. Write “Why?” on chalk board.

- Invite discussion on the phenomenon of static electricity.

- Set up equipment as shown.

- Rub plastic rod with wool (in one direction) 8-10 times.

- Bring rod near one straw piece and observe the reaction.

- Touch straw piece with fingertip.

- Repeat steps 2-3 several times.

- Rub rod with wool again.

- This time touch one straw piece with rod to observe the reaction.

- Touch straw piece with fingertip.

- Repeat steps 6-8 several times.

- Bring piece of wool near straw pieces and observe.

- Bring plastic rod near straw pieces and observe.

Follow-Up Questions for Students

- Wool rubbed on plastic gives up electrons to the plastic rod. What is the charge on the rod?

- How did the straw pieces act when the charged rod was brought near one of them?

- Your body can accept a small electrostatic charge. What was the charge on the straw piece after you touched it?

- How did the straw pieces act when the charged rod touched one of them?

- How did the straw pieces react to the piece of wool?

- How did the straw pieces react to the uncharged rod?

- Explain the reactions observed in this activity.

ACTIVITY #4:

The Need For the Establishment of the University System

1 class period

Background Info for Activity

When the US was a very young and emerging nation, growing by leaps and bounds, the physical boundaries began changing and there was a need to improve the educational facilities. Two statesmen of the time searched further for knowledge: Thomas Jefferson assisted in founding the University of Virginia and Benjamin Franklin was instrumental in establishing the University of Pennsylvania.

MATERIALS:

COLORED PENCILS, US MAP

PROCEDURE:

- Have the students trace the most direct route to each of the universities from their own home towns. They will label states crossed, state capitals, major rivers, and major mountain chains.

- The students will do a biographical summary of Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin which should show that these two men were not only statesmen, but were also involved in the development of the sciences and mathematics of a young country.

ACTIVITY #5:

Research: T. Jefferson, B. Franklin & B. Thompson (Count Rumford)

2-3 class periods

MATERIALS:

APPROPRIATE RESOURCE MATERIALS

PROCEDURE:

- Divide the class into 6 small groups.

- Assign each group one of the following topics to research:

- historical, political, and biographical information about Thomas Jefferson

- b) major scientific contributions of Thomas Jefferson

- historical, political and biographical information about Benjamin Franklin

- major scientific contributions of Franklin

- historical, political, and biographical information about Benjamin Thompson (Count Rumford)

- major scientific contributions of Rumford

- After the students become “experts” on their topic, rearrange the groups so that the new group is composed of one expert on each topic. The students teach the members of their group about their topic.

- Discuss the interaction of science, society and technology in historical development.

ACTIVITY #6:

Work and Temperature (Count Rumford) Experiment

(For Small Group or Teacher Demo)

30 Minutes

MATERIALS:

GRADUATED CYLINDER, PLASTIC FOAM BOWL (PLASTIC FOAM IS NEEDED TO PREVENT HEAT LOSS), THERMOMETER, EGGBEATER, HAND-HELD WATCH OR CLOCK THAT INDICATES SECONDS, GRAPH PAPER

PROCEDURE:

- Students are to follow the proceeding instructions:

- Put 200ml of water in a plastic foam bowl. Measure the temperature of the water. Set up a table showing time and temperature. Record your reading.

- Beat the water VIGOROUSLY with the eggbeater one full minute (have your partner hold the bowl so it does not slip). IMMEDIATELY measure the temperature of the water and record the reading.

Note: Accurate measurement is important because the temperature will not change a great amount.

- Repeat step 2 four times.

- Plot temperature readings on graph paper (horizontal axis-minutes, vertical axis-temperature, in °C).

Follow-Up Questions for Students:

- What is the temperature of the water at the beginning of this activity?

- How does the temperature change after the water has been beaten for one minute?

- What does your graph show about the relationship between work and temperature?

- Calculate the average change in water temperature per minute of beating.

- Compute the amount of work done on the water. The energy required to raise 100ml of water 1°C is 420 joules of work.

- How does this experiment support Count Rumford’s beliefs about heat?

Bibliography

Dictionary of Scientific Bibliographies/Physics. Merrill.

Greene, John. American Science in the Age of Jefferson. Ames: Iowa State UP, 1984. 12-13.

Hewitt, Paul. Conceptual Physics. Addison-Wesley.

Introduction to Physical Science. Addison-Wesley.

Moyer, A. E. “Benjamin Franklin: ‘Let the Experiment be made.'” The Physics Teacher 14 (1976): 536-545.

Seldes, George. The Great Thoughts. Ballantine Books, 1985.