Scroll down to read the Arthurian episode in the medieval Life of St. Efflam

Arthur and/or St. Efflam fighting a dragon

It turns out that there are TWO sculptures in the Breton church of St-Jacques at Perros-Guirec which have been interpreted as Arthur and St. Efflam fighting a dragon. It is not impossible that the two sculptures, one of which represents violent conflict an the other some kind of deliverance, could be related to each other; however, their styles are quite different.

On the south portal of the church is a sculpture showing, apparently, two men attacking a dragon; in the nave is a sculpture showing a man with a crozier apparently helping a naked man away from a coiled mass which could be a dead dragon. Recently a paper was delivered at a conference by Esther Dehoux (histoire médiévale, Poitiers),”« Pour la colère du plus grand roi des Bretons» ? Arthur, l’évêque, l’apôtre et les dragons au portail de l’église de Perros-Guirec,” a title which suggests (For the anger of the greatest king of the Britons? Arthur, the bishop, the apostle, and the dragons on the Perros-Guerec church portal) that current opinion identifies the sculptures on the porch as representing Arthur, the dragon, and holy men.

De la Monneraye’s original 1849 article on the church can be read here: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k2074644.image.f305.langFR . He describes both capitals, but it is the external (porch or portal) one which he identifies as the story of Efflam.

Below are three photos. two of the porch sculpture and one of the nave sculpture.

The first two are of the porch (portal) sculpture, courtesy of Chris Lovegrove. Chris’s description: “the image of a helmeted warrior with a shield with, to the viewer’s right, another figure with a sword (a squire, perhaps?), confronting a headless monster crawling around the capital.” It looks as if the monster would originally have had a head, though.

De la Monneraye’s remarks on this capital (p. 159): “Six columns take the weight of the archivolt [of the portal], two by two; they are crowned by very strongly flared capitals, decorated with people or animals. The first capital on the left represents an episode in the life of Saitn Efflam: great Arthur, head of the knights of the Round Table, had been fighting vainly against a terrible dragon which had laid waste the parish of Plestin and the whole shoreline; Efflam, recently arrived from the British coast, comes on the scene just as the warrior is about to succumb from exhaustion and the torments of a cruel thirst. Arming himself, according to the legend, with the sign of the Cross, he touches with his apostolic staff the monster, which withdraws in terror and throws itself into the sea, to disappear forever. This last part of the scene is the subject of the first capital.” Loomis indicates this page as the description of the other capital (#2, below). However, there is no question but that this is the outermost capital on the left of the portal, and therefore the one De la Monneraye identified as portaying Efflam. Oddly enough, it does not correspond very well to his description, since one sees Arthur actively fighting the dragon and the figure behind him has a sword, not something which could be interpreted as “an apostolic staff.” Perhaps there was an extension of the scene on lost portions of the capital.

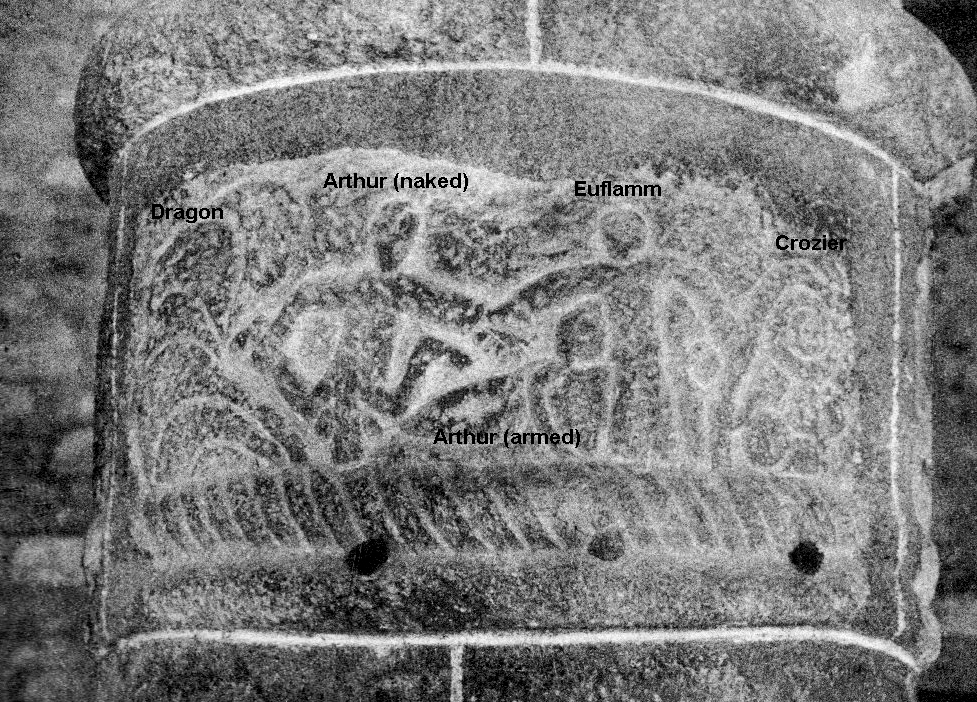

The nave sculpture (above) is also a carving on a capital, this one inside the church. Loomis (p. 31) mistakenly cites De la Monneraye’s description of the portal capital (#1 above) as applying to this one, although he is aware that other scholars believe it is the portal capital which is indicated. According to Loomis, we see Arthur, having exhausted his shield and arms, being drawn away from the slain dragon by St. Efflam, identified by his crozier.

De la Monneraye’s description of this portal: On p. 160, the author enters the church (“En penetrant dans l’eglise…) and finds there more capitals, but not flared (there is no doubt a technical in English for this; anyway, the ones outside are wider at the top than at the bottom, while the ones inside are cylindrical). He remarks that the sacrifice of Abraham is carved on one of these, and then: “On another capital of the same style, we see a man whose pose and form seem to personify the Lustful, the Debauched. A second character, standing beside him and holding in his left hand a curving crozier, reaches out with his right to lift up the other man, to draw him closer and away from vice.”

As Chris Lovegrove noted on the list, the arrangement of the figures might also suggest the Harrowing of Hell (Christ, with a bishop’s crozier instead of the usual triumphant cross, drawing Adam from Hell, Hell being represented as a dragon).

Many more ( recent, color) pictures of of St-Jacques and its 12th-century capitals are available on the web.

Sorrento66 photostream includes 12 photos of capitals (exterior and interior) and of the church in general, including both of the capitals above.

Certif 3’s album “Visiting a few churches in Brittany and France” includes 17 photos of the church, including many nave capitals.

Renaud Camus’s photostream–nice picture of the church and another of the “Arthurian” portal capital.

Life of Efflam (also called Euflam, Eflam, Eflamm, etc.)

This life of a Breton saint may have been written as early as 1090 or so, but maybe considerably later. Its presentation of Arthur makes it clear that the author does not know anything about King Arthur.

The story so far: Efflam, born a king’s son in Ireland, has decided to leave his wife (without consummating the marriage). He finds a ship and boards it with some holy men as companions. It steers by God’s will and lands them in Brittany, on a beach near a huge cave (today’s Plestin-les-Grèves). They see a monster come out of the cave, walking backwards so that its footprints cannot be tracked (see the story of Hercules and Cacus, Aeneid VIII).

[The monster] was careful to avoid Arthur, a very strong man, who in those days was hunting monsters in that part of Brittany. Finally, by God’s will, the wicked wily thing was outsmarted. Arthur, concentrating his whole mind on its activities, tracked it down. While he was investigating the rocks where it might be hiding, he met the holy men on the shore; he expressed admiration at their courage in living in such a horrible solitary wasteland. He asked them carefully who they were and where they had come from; as he questioned them, they told him about the monster and pointed out its cave. Arthur was delighted by the arrival of the holy men and rejoiced with all his heart at the indication of the monster’s cave. So often he had gone away sad, humiliated as if the monster had beaten him, because he could not [find it to] overcome it. He armed himself therefore with a triple-knotted club; with a shield covered by a lion-skin he defended his brave chest. Then, manfully, one man fighting for all, he attacked the public enemy.

Against him, the horrible monster protected itself with its own weapons. Moreover, it attacked Arthur first, indignant that any man should come hunting it, since it had won so many battles against so many groups of people. So, attacking with all its strength, it struck Arthur’s strong shield, which it easily pierced with its sharp claws. No surprise: even the hard stones had been scratched by their points, so that the whole area bore witness by these marks. Arthur, having pulled his body back, remained unwounded, and, angry now, he struck his enemy fiercely. He could have knocked down walls with a blow like that, but the enemy, protected by its hard skin, did not receive a mortal wound. All the same, it felt to the depths of its being the terrible pain of the blow. All day they fought in this way, but the serpent did not get a lethal wound.

Arthur, realizing that night was coming, put off the battle until the next day. He went back to the holy men, tired from his work and weak from the struggle; his mouth was parched by a powerful thirst, and he asked the men for water. Efflam replied for them all: “My lord, we do not have water, and we, like you, need it; therefore it remains for us to ask our God for it.” Arthur praised the righteous advice of the good man. Bending their knees, they all knelt on the ground. Stretching out his whole body, Efflam, the voice of all his companions, prayed, saying: “God, your immutable power created everything without preexisting matter, and all things serve you according to their properties, and at your order all things change their qualities, so that hard things melt to softness and rough things are made smooth. Proclaim your strength over us, and, as you once ordered water to flow from a rock in the desert for the thirsty people when your servant Moses prayed [Exodus 17:1-7], so, Lord, deign in your great mercy to pour forth water for us.” When he had finished praying, he climbed up on a tall rock, made a little sign of the holy cross, and struck the stone. An abundance of water burst forth into the air. Giving thanks, the thirsty man [Arthur] drank this water, and then threw himself down at the feet of Saint Efflam, beseeching him with humble prayers to deign to bless him with a laying on of hands, and pray with prayers for him to God. [He needed such prayers,] since he often undertook deeds to free people where he was in doubt of his life. Efflam, that man of God, blessing him, promised him the gift of prayers.

Arthur withdrew, filled with joy, his thirst gone, his strength restored by the divine drink, fortified by the holy blessing. Confident in the strength of the holy man, he left the question of his battle with the monster up to him. The athlete of Christ [Efflam; see 1 Corinthians 9:25], armed with the weapons of faith [Ephesians 7:10-17], ordered the horrible monster to come forth. So that he might strengthen his companions’ faith, he spoke thus with a loud voice: “Lord Jesus Christ, you gave your disciples such power that they might bind and loose whatever they wished [Matthew 16:19], and indeed you said of them, ‘they order demons to flee, and they remove serpents’ [Mark 16:17-18]. Order the departure of this serpent so that this region, freed from such a plague, will be able to give you praise and thanks.” And when they replied “Amen” the monster, which had drawn itself up on a rock, rolled its eyes in all directions and gave forth a cry mixed with a deep miserable sigh, a noise which made far-off places tremble. Then, hanging its head, it brought forth a bloody vomit from its sobbing mouth and nostrils. In witness to this miracle, the rocks in that place seem to shine red as if with recently shed blood. Then, with the holy men watching, it went down to the sea, stretching itself out on the wave, and left, never to return. By these two miracles, God wished to show the power of his servant Efflam at the beginning of his exile: that a man who left his father and mother, and renounced all he possessed in order to follow Him righteously, could have confidence in His grace.

Translations J. Shoaf