While Arthur is usually assumed to have been a Briton leading the British kings, one medieval author refers to him as a Pictish general, from the area north of Hadrian’s Wall (i.e. present-day Scotland). This author is Lambert of St Omer, who compiled his encyclopedia Liber Floridus before 1120 (that is, before Geoffrey of Monmouth had written his History of the Kings of Britain, which made King Arthur famous). Lambert is clearly relying on the 9th-c. Historia Brittonum (“Nennius”), written in Wales, for much of his material, but he had also heard about a round “palace” in Pictland dedicated to the local hero Arthur, and he inserted information about this Arthur in a couple of places, combining it with material from Nennius and also attributing it to Bede.

The palace in question is probably the round Roman temple near Falkirk, Scotland, which was destroyed in 1743. It was known as Arthur’s O’on (Arthur’s Oven), though it had also been associated with Julius Caesar, the god Mars, etc.

I present here all the Latin texts referring to Arthur from Nennius, out of order, and the corresponding passages from Lambert. Translations below.

From the Historia Brittonum

( Latin transcribed by Judy Shoaf from Coe & Young, Celtic Sources for the Arthurian Legend)

From ch. 73, Mirabilia Britanniae

Est aliud mirabile in regione quae dicitur Buelt. Est ibi cumulus lapidum, et unus lapis superpositus super congestum cum uestigio canis in eo. Quando venatus est porcum Troynt, impressit Cabal, qui erat canis Arturi militis, vestigium in lapidi, et Arthur postea congregauit congestum lapidum sub lapide in quo erat vestigium canis et uocatur Carn Cabal. Et veniunt homines uero et tollunt lapidem in un manibus suis per spatium diei et noctis, et in crastino die inuenitur super congestum suum.

Est aliud miraculum in regione quae dicitur Ercing. Habetur ibi sepulchrum iuxta fontem qui cogniminatur Licat Amr, et viri nomen qui sepultus est in tumulo, sic uocabatur Anyr, filius Arturi militis erat et ipse occidit eum ibidem et sepeliuit. Et ueniunt homines ad mensurandum tumulum in longitudine aliquando sex pedes aliquando nouem, aliquando duodecim, aliquando quindecim, in qua mensura metieris eum in ista vice, iterum non inuenies eum in una mensura et ego solus probaui.

From Ch. 56, quoted out of order to fit with Lambert’s version.

……Tunc Arthur pugnabat contra illos in illis diebus cum regibus Brittonum sed ipse dux erat bellorum. Primum bellum fuit in ostium fluminis quod dicitur Glein. Secundum et tertium et quartum et quintum super aliud flumen quod vocatur Dubglas et est in regione Linnius. Sextum bellum super flumen quopd vocatur Bassas. Septimum fuit bellum in silua Celidonis, id est Cat Coit Celidon. Octauum fuit bellum in castello Guynon, in quo Arthur portauit imaginem sanctae Mariae perpetuae uirginis super humeros suos et pagani uersi sunt in fugam. In illo die caedes magna fuit super illos per uirtutem Domini Nostri Iesu Christi et per uirtutem sanctae Mariae Virginis genitricis eius. Nonum bellum gestum est in urbe Legionis. Decimum gessit bellum in littore fluminis quod uocatur Tribruit. Vndecimum factum est bellum in monte qui dicitur Agned. Duodecimum fuit bellum in monte Badonis, in quo corruerunt nongenti sexaginta uiri de uno impetu Arturi et nemo prostrauit eos nisi ipse solus. Et in omnibus bellis uictor erat.

[This text immediately precedes the account of Arthur’s battles quoted above.] In illo tempore Saxones inualescebant in multitudine et crescebant in Britannia. Mortuo autem Hengesto Octha filius eius transiuit de sinistrali parte Britanniae ad regnum Cantorum et de ipso orti sunt reges Cantorum. Tunc Arthur pugnabat contra illos in illis diebus cum regibus Brittonum sed ipse dux erat bellorum. [as above]

Liber Floridus of Lambert of St Omer

(Latin transcribed by Charles Gunther from an article by David Dumville)

From Ch. 52, Miranda Britannie

Est tumulus lapidum in Brittannia in prouintia Buelth, et unus lapis superpositus et uestigia canis qui uocabatur Cabal Arturi militis impressa lapidi, quando uenatus est aprum Trointh in loco qui dicitur Carmy Cabal, eo quod Artur sub lapide illo tumulum fecerit. Homines uero illius prouintie dum tollunt de tumulo lapidem et abscondunt biduo, die tercio inuenitur super tumulum.

Est sepulchrum in Brittannia in prouintia Ercing iuxta fontem Lycatanir filii Arturi militis qui uocabatur Anyr, in quo sepeliuit eum Artur. Dum autem ueniunt homines ad mensurandum sepulchrum, habet in longitudine mensuram aliquando Vque pedum aliquando VIII, aliquando XI, aliquando XV, numquam una uice sicut altera.

Est palatium, in Brittannia in terra Pictorum Arturi militis, arte mirabili et uarietate fundatum, in quo factotum bellorumque eius omnium gesta sculpta uidentur. Gessit autem bella XII contra Saxones qui Brittanniam occupauerant. Primum bellum fuit in ostium fluminis quod dicitur Gleuy. Secundum uero et tercium et quartum et quintum super flumen Dubglas. Septimum in silua Celidonis. Octauum in Castello Guynon, in quo bello portauit Artur imaginem sancte Marie super humeros sues et pagani uersi sunt in fugam. In illa die cedes magna fuit de paganis per uirtutem Domini Nostri Iesu Christi et sancte Virginis Genitricis eius. Nonum bellum gestum est in urbe Legionis. Decimum in littore fluminis quod uocatur Tribuith. Vndecimum in monte Agned. Duodecimum in monte Badonis, in quo bello corruerunt nongenti sexaginta uiri de uno impetu Arturi auxiliante Domino Iesu Christo.

From ch. 57, Historia Anglorum a beato Beda venerabili presbitero composita.

In illo tempore Saxones inualescebant in multitudine et crescebant in Britannia. Mortuo autem Hengesto Octha filius eius transiuit de sinistrali parte Britannie ad regnum Cantorum et de ipso orti sunt reges Cantie. Tunc Arthur dux Pictorum interioris Britannia regens regna, fortis uiribus, miles acerrimus, uidens Angliam undique impugnari et bona terre diripi multosque captiuari ac redimi et ab hereditatibus expelli, cum Britonnum regibus feroci impetu Saxones aggreditur et in eos irruens pugnabat uiriliter, dux bellorum XIl eis existens ut RETRO scriptum in est VIII ue folio.

English for Historia Brittonum

(tr. J. Shoaf, in an attempt to match the Liber Floridus and show what is borrowed and what is changed):

from Ch. 73, Wonders of Britain

There is another wonder in the region which is called Buellt. There is a mass of stone and one stone placed on the top of the pile with the footprint of a dog on it.When Cabal, who was the dog of Arthur the soldier, hunted the pig Troint, he pressed his footprint into a stone, after which Arthur gathered the pile of stones underneat the stone on which was the footprint of the dog, and it was called Carn Cabal. And men come, and carry the stone in their hands for a space of a day and a night, and on the next day the stone is found on the pile.

There is another wonder in the region which is called Erging. A grave is there next to a spring which is called Llygad Amr, and the name of the man who is buried there is Amr the son of Arthur the soldier, and this same man killed him and buried him there. And men come to measure the tomb and it is sometimes 6 feet long and sometimes 9 feet, sometimes 12, sometimes 15. At whatever length you measure it at one time, you will not find it again at the same length and I myself have tested this.

from Ch. 56, out of sequence:

….Then Arthur fought against them in those days with the kings of the Britains but he himself was the leader of battles. The first battle was in the east at the river called Glein. The second, the third, the fourth, and the fifth on the river Dubglas in the region of Linnius. The sixth battle was by the river that is named Bassas. The seventh battle was in the forest of Celidon, that is Cat Coit Celidon. The eighth battle was in Castle Guinon, in which Arthur carried an image of St. Mary, the eternal virgin, on his shoulders and the pagans were turned in flight. In that day there was great slaughter of thm through the power of Our Lord Jesus Christ and and through the power of St. Mary, his Virgin Mother. The ninth battle was fought in the City of the Legion. He fought the tenth battle on the bank of the river called Tribruit. The eleventh battle was waged on the mount called Agned. The twelfth battle was on mount Badon, in which battle 960 men fell in a single attack by Arthur, and no-one brought them low except he. He proved victorious in all his battles.

[This text immediately precedes the account of Arthur’s battles quoted above.] In that time the Saxons grew strong and multiplied in Britain. At the death of Hengest, his son Octa moved from the left part of Britain to the kingdom of the Canti (Kentish) and from him arose the kings of Kent. Then Arthur fought against them in those days with the kings of the Britains but he himself was the leader of battles. [as above]

English for Liber Floridus

(tr. J. Shoaf)

from Ch. 52, Wonders of Britain

There is a mound of stones in Britain in the province of Buelth, and one stone placed on the top and the footprints of a dog called Cabal belonging to Arthur the soldier imprinted on the stone, when he came hunting the boar Trointh in the place called Carmy Cabal, and under that same stone Arthur made that mound. And it’s a fact that when men of that province take the stone from the mound and hide it for two days, on the third day it is found on top of the mound.

There is a tomb in Britain in Ercing province near the spring of Lycatanir [or Lycat Anir] which belongs to the son of Arthur the soldier who was called Anyr, in which Arthur himself buried him. Now, when men come to measure the tomb, it measures in length sometimes a total of 5 feet, sometimes 8, sometimes 9, sometimes 15, never the same one time as another.

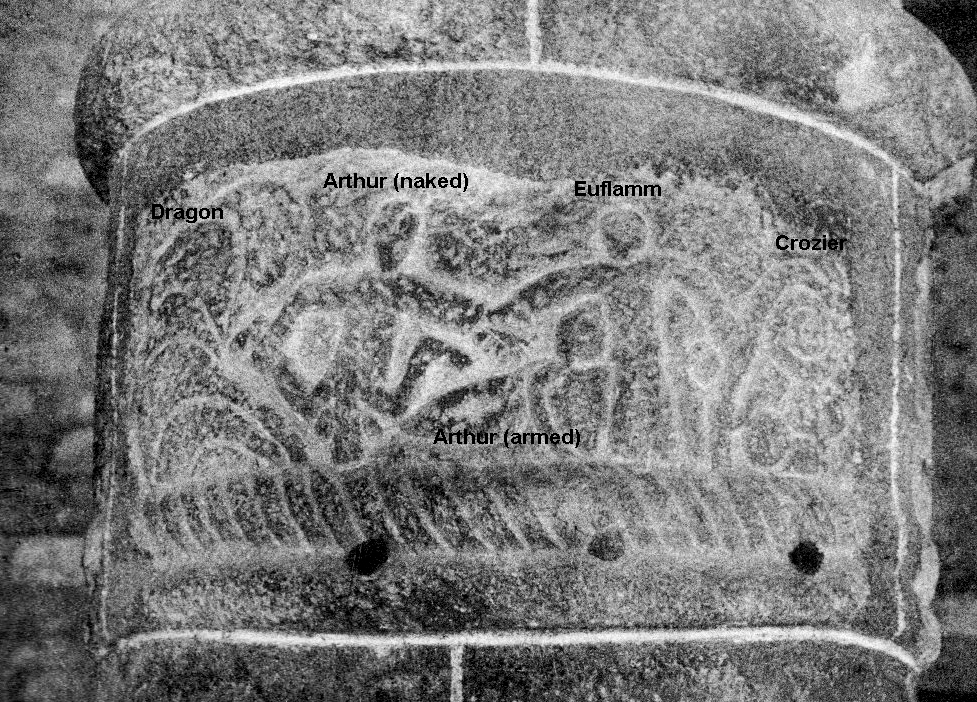

There is a palace, in Britain in the Picts’ land, of Arthur the soldier, built with wondrous art and variety, in which may be seen sculpted all his acts both of construction and in battle. It shows in fact the 12 battles against the Saxons who had occupied Britain. The first battle was at the mouth of the river called Gleuy. The second indeed and the third and the fourth and the fifth on the river Dubglas. The seventh in the forest of Celidon. The eighth in Castle Guinon, in which battle Arthur carried an image of St. Mary on his shoulders and the pagans were turned in flight. In that day there was great slaughter of pagans through the power of Our Lord Jesus Christ and his sainted Virgin Mother. The ninth battle was fought in the City of the Legion. The tenth on the bank of the river called Tribuith. The eleventh on mount Agned. The twelfth on mount Badon, in which battle 960 men fell in a single attack by Arthur, with the help of the Lord Jesus Christ.

from Ch. 57, History of the English composed by Blessed Bede the venerable priest

In that time the Saxons grew strong and multiplied in Britain. At the death of Hengest, his son Octa moved from the left part of Britain to the kingdom of Cantus (Kent) and from him arose the kings of Kent. Then Arthur the leader of the Picts, directing kingdoms inland in Britain, with strong men, this fiercest soldier, seeing England [Anglia] everywhere beaten in battle, good lands taken away, many enslaved and redeemed and expelled from their inheritance, with the kings of the Britons he came against the Saxons with a ferocious attack and rushing upon them fought manfully, the leader in 12 battles, the same [?] as is written above on the 8th leaf [of this manuscript]

.