Babies and children are, of course, the subject par excellence of dollmakers everywhere. The primitive guardian dolls, amagatsu and hoko, which were meant as twins or doubles of the baby, to confuse evil spirits, or course represent children. The oldest sculpted figures identifiable as dolls (rather than religious icons) are the Saga ningyo, These were made like religious or memorial images, carved of wood and covered with gofun, brilliant paint, and gilding, but they portrayed cheerful little boys instead of hieratic, awe-inspiring figures. It is difficult, even so, to draw the line between what may have been a memorial figure of a deceased child and a work carved to amuse as well as please any viewer.

An important figure in the portrayal of children is the Chinese child, or karako . This is a little boy, often wearing a Chinese tunic and shoes, with his hair done in two knobs, one on either side of his face. Karako were popular in 17th-century Japanese art, and show up in Saga ningyo and also as acrobats the automatons or performing dolls displayed on festival carts on religious or civic holidays. These automatons were also made of wood covered with gofun.

Gosho dolls

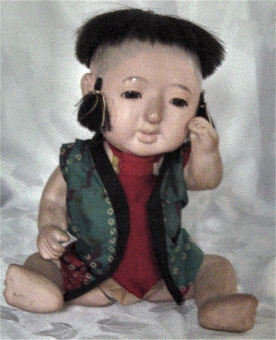

In the 17th and 18th century, there developed a representation of a Japanese baby boy, the Gosho ningyo, which was primarily secular, though it probably had some implications for fertility when given, for example, as a wedding gift. The classic Gosho doll has a big round head, possibly with a bit of hair carved or painted on it, and textile clothing (usually not much clothing–a vest or little chest-protector is normally adequate). He may be depicted crawling on all fours, or sitting playing with some toy. Smaller Gosho dolls may be standing, especially in the 19th and 20th centuries. The spherical white head with small features bunched together lent itself to many kinds of satirical depictions of baby heroes, generals, actors, and other adult types. On the other hand, the Gosho type clearly influenced many modern dollmakers working on creating natural-looking dolls representing babies and children.

Ichimatsu dolls

Gosho dolls and other early types had limited play value. Most of them were frozen in a single pose; some had a very specific, limited joint which allowed a particular type of movement (the child puts on a mask, or beats a drum, for example). In the 18th century, a different doll-puppet hybrid developed, whose limbs were jointed, making it easy to change the doll’s clothing or pose the doll. This type of doll was well adapted to play of all kinds, and jointed babies, children, and adults became extremely popular. The jointed play doll is called Ichimatsu ningyo, after a popular Kabuki actor of the 18th century, Sanogawa Ichimatsu. There were in fact 3 actors who used this name, the first having been born around 1722, the second taking the name when the first retired, and so on. Depictions of the actor by Masonobu and Toyonobu show him holding up a puppet on both hands, representing in accurate detail either himself or another Kabuki-style character; it seems possible that he was a pioneer in developing these jointed miniatures, or at least an important patron.

The most elaborately jointed ichimatsu are the mitsu-ore (three-fold) dolls. They may represent an adult or a child, a boy or a girl (often anatomically correct). The doll is usually jointed at knees and hips, and perhaps the ankles as well; it can be put into a sitting (i.e. kneeling) position. The most elaborate ones are all wood, with hollow thighs to stabilize the sitting position. The dolls are finished in gofun and dressed in several layers of clothes, sometimes with various accessories. Cheaper types of dolls have cloth joints, glued onto the wooden or paper-mache limb sections to allow for floppy poses. Finally, there are baby dolls with five-piece strung bodies, whose chubby bent limbs can be moved to allow them to sit (in the Western meaning of the word) or lie down. These dolls may be referred to as Daki ningyo (cuddly doll), and seem to have evolved in the 1930s.

An ichimatsu representing a child may go under a number of names. Tokebei Yamada, in Japanese Dolls (1955), calls them Yamato ningyo, “truly Japanese dolls.” A doll representing a little girl dressed in a long-sleeved kimono (worn nowadays for special festivals) can be called a furisode ningyo, as this kimono reserved for young girls is called furisode. The term warabe ningyo (“child doll”) can also be used, though it also covers non-jointed dolls.

Ichimatsu or daki dolls typically have gofun skin tinted pink. Baby or child dolls may have mechanisms in the abdomen which, when pressed, emit a crying noise. Girl ichimatsu have wigs of human or horsehair, while the boys usually have painted hair (or a blue head indicating the hair has been shaved off), though baby boys may have bits of real hair inserted to represent what is left after the baby’s head is shaved. The dolls may be dressed in kimono made of old clothes or leftover human-size yardage, or in cloth with appropriately sized patterns; miniature accessories may be added.

In the second half of the 19th century ichimatsu dolls became very popular in the West, and were exported from Japan; some of them were big, beautiful babies, others cheap little “Jap dolls” with paper joints and sketchy features. They captured the imagination of Western artists, and were quickly imitated by dollmakers who saw the advantage of producing a poseable doll for play.

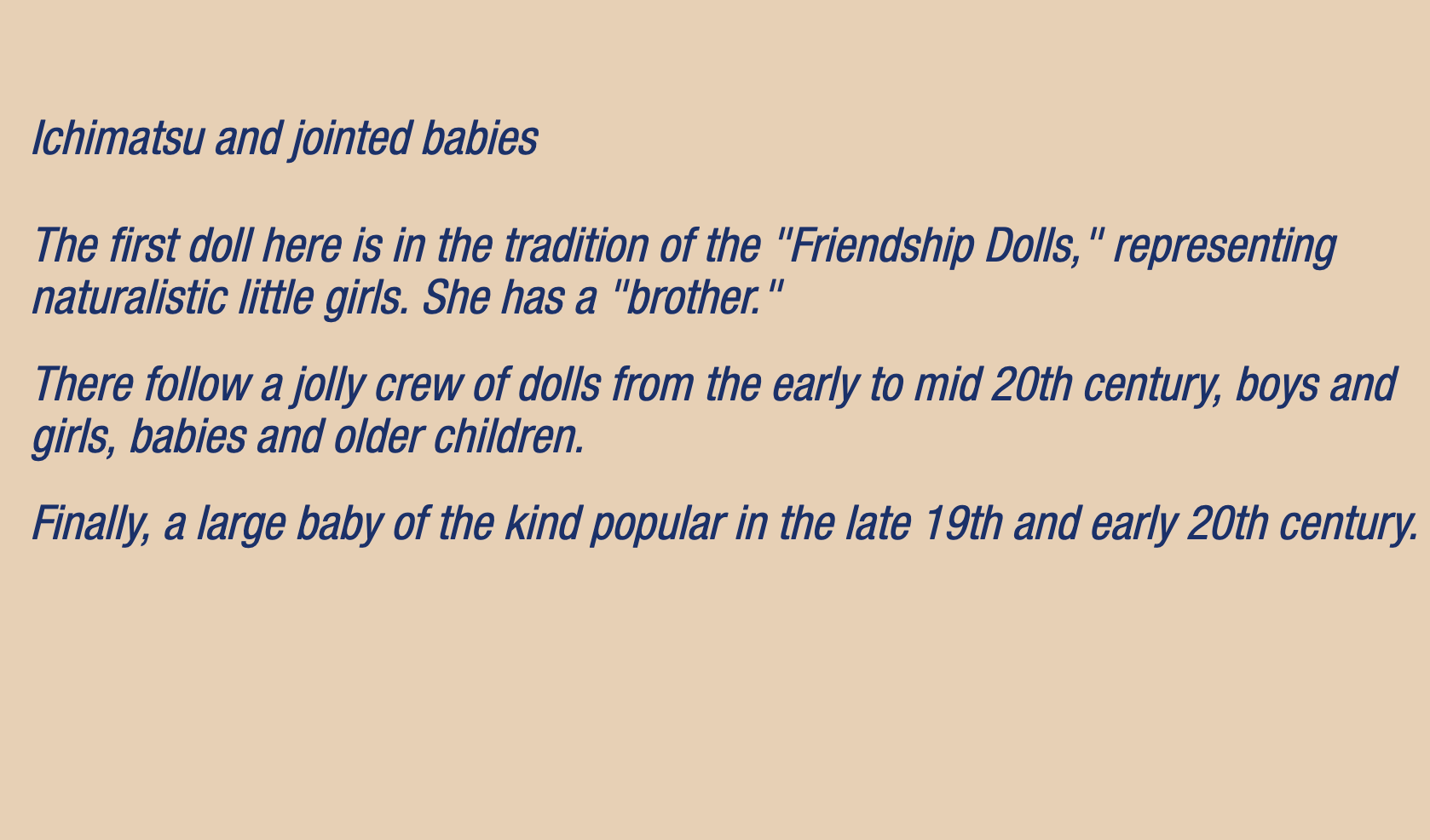

Friendship Dolls

The most important ichimatsu of all were the dolls sent from Japan to the children of the United States in 1927 as part of the Friendship Doll Exchange.

This initiative began as a gesture of goodwill towards Japan, conceived of by the missionary Sidney Gulick. In 1926, 12,739 dolls (composition dolls with wigs and sleep eyes and ma-ma voices) were collected from American children and sent to Japan as a token of international friendship. Most of the dolls were distributed to schools. In return, “the children of Japan” had 58 large dolls made to be sent to the U.S.

These Torei Ningyo (ambassador dolls) represented little girls in the furisode or long-sleeved kimono, and were of superb quality. Each girl was 32″ tall and elaborately dressed, and often came with her own furniture, tea-set, and various accessories. They were named for the prefectures and provinces of Japan, and for a few large cities which contributed to be represented; the most beautiful doll was Miss Dai Nippon, representing the whole country The dolls traveled around the country, and in the course of display some of them exchanged kimono, accessories, and even the stands which gave their names.

During the war, many of these dolls were hidden away or destroyed in both countries, though Miss Kagawa remained on display in Raleigh, North Carolina, with this notice:

The Japanese made an insane attack upon the American Territory of Hawaii on December 7, 1941.

With a grim determination we now are committed to stop for all time Japanese agression. This has no bloodthirsty implications to destroy peoples as such. We still believe in peace, good-will, to live and let live.

Men, women, and children of Japan have this good-will, but they have now been dominated by ruthless leaders. Proof of such latent good-will are the Friendship Doll Exhibits exchanged between children of the United States and Japan and shown as here in museums in both countries.

In Japan, the “blue-eyed dolls” from America were officially considered and treated like spies or enemies. They were burned, sometimes after being bayoneted. Nevertheless,there exists a photo from a school in Hokkaido of a 1942 Hina Matsuri celebration incorporating one of these dolls, and decades after the war some dolls that had been hidden away were brought back out to be honored again.

Since the 1980s there has been renewed interest in the two sets of dolls in both countries. 45 of the 58 Japanese ningyo are known to have survived, some in public collections and a few in private hands, and more than 20 of them have visited Japan and received honors, repairs, new outfits or companions.

See Bill Gordon’s page on the Friendship Doll Exchange, which lists all the dolls whose locations are known. Alan Scott Pate, owner of Miss Fukushima, has an article about her online which outlines some of his research on the subject.