Traditional dolls in Japan may be made to resemble human beings, either at rest or in action, in a fairly realistic way: ichimatsu dolls represent children or sometimes adults, and theatrical dolls or costume dolls are usually realistically proportioned. However, other types of dolls represent the human form in a highly stylize way. They have specific outlines that are recognizable and identify the doll immediately as a particular type; these formats may then be changed to produce a kind of satire or meditation on the nature of the doll and its normal role in the lives of children or adults.

1. Amagatsu (Heavenly Child). This type of doll is mentioned in the Tale of Genji (ca. 1000) as a guardian doll for newborns, kept at all times with the child. The reference is thought to be to a cross-shaped figure, made of by fixing wooden or bamboo rods in a T-shape to form a body and arms, with a cloth-covered head attached. The amagatsu may have been large enough to “wear” the child’s clothing; at any rate, the doll functioned as a kind of twin to the child, meant to distract evil spirits (e.g. diseases) from its living counterpart. It would be burned when the child came of age. The cross-shaped doll seems to survive in the male doll of the tachibina pair, discussed below.

2. Hoko (Crawling Baby). This is another guardian doll type, made by sewing a rectangle of cloth in such a way as to form 4 limbs, all of which point in the same direction. Hoko dolls had round stuffed heads, sometimes with long hair attached. This format is still used for red sarubobo (monkey dolls) which have a guardian function. Because this doll is soft and cuddly, it was more likely to become a toy for the baby than the bamboo amagatsu. The shape was considered to represent a crawling baby, and what sometimes seems like clumsiness in the depiction of crawling babies by ningyo artists is in fact a reference to the hoko format. Tiny hoko dolls remain a popular craft.

3. Cylindrical dolls. The obvious example of a cylindrical doll is the kokeshi (“poppy-seed child”) doll. Kokeshi dolls, which consist of a lathe-turned wooden cylinder body and sphere head, are still made, as they have been since ca. 1800. They were originally souvenirs of the Tohoku hot-springs area, but could be used as offerings to the gods, possibly representing children who had died. There are a certain number of “classic” kokeshi styles, distinguished by experts through slight variations in shape, construction, and painting. The basic idea of the lathe-turned doll with spherical head, however, has been explored by artists in many ways, so that one finds nesting kokeshi, rounded neckless kokeshi, and kokeshi positioned in little scenes of daily life or of legend.

3. Cylindrical dolls. The obvious example of a cylindrical doll is the kokeshi (“poppy-seed child”) doll. Kokeshi dolls, which consist of a lathe-turned wooden cylinder body and sphere head, are still made, as they have been since ca. 1800. They were originally souvenirs of the Tohoku hot-springs area, but could be used as offerings to the gods, possibly representing children who had died. There are a certain number of “classic” kokeshi styles, distinguished by experts through slight variations in shape, construction, and painting. The basic idea of the lathe-turned doll with spherical head, however, has been explored by artists in many ways, so that one finds nesting kokeshi, rounded neckless kokeshi, and kokeshi positioned in little scenes of daily life or of legend.

The cylindrical shape itself may well date much earlier, though, perhaps to paper construction of an armless doll.

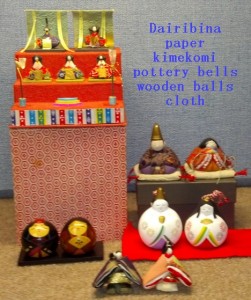

4. Tachibina (“standing hina”) can be made of paper at home, and have been for centuries; they are considered to be the earliest form of the dairi-bina or “imperial couple” displayed on Hina Matsuri (the Doll Festival, March 3). They represent a man (large, with outstretched protective arms) and a woman (smaller, armless). They are thought to echo the contrasting shapes of the amagatsu and hoko doll.

When made of paper or inexpensive materials, they are appropriate for the nagashi-bina purification ceremony, the ancestor of Hina Matsuri, in which dolls are touched or rubbed to absorb one’s sins, and then thrown into a river. A single doll, used as a kind of proxy for the person being purified is used for this ceremony in the Tale of Genji, but modern nagashi-bina usually use pairs of dolls.

In the years 1000-1600, there is intermittent evidence that paper dolls were made to play with or to give as gifts on the third day of the third month, the festival associated with nagashi-bina purification rituals. By the 17th century, they were probably being made professionally using rich cloth instead of paper, with complex heads, but by the end of that century we are told that commoners also made the dolls so their daughters could celebrate the third day of the third month with doll play.\.

In the 20th century, tachibina came to be made of various more durable materials (kimekomi, wood, pottery, or complex construction like hina). As a design element on clothing, boxes, or plates, they are an emblem of the Hina Matsuri, but they also evoke the idea of a happy marriage.

5. Classic dairi-bina or hina dolls. In the 17th century dollmakers developed a pyramidal format for a male-female doll pair to be displayed on March 3. They represent the seated (i.e. kneeling or sitting cross-legged on a cushion) courtiers in the Emperor’s dairi, or residence at his palace. Each doll could be made of a combination of materials–to some extent these dolls were and are pieces of cloth sewn into a 4-sided pyramid, stuffed to keep their shape with whatever materials are available, to which heads, hands, and (for some male dolls) feet are added. Although fashions in head-shapes and costume design have varied over the centuries, this form is still instantly recognizable.

6. Gosho (Imperial Palace) dolls represent baby boys and are composed of white spherical elements. This format echoes Buddhist ideals. Gosho dolls are made of clay or wood or composition covered with gofun (oyster-shell paste). They were first made early in the 17th century and, like the dairi-bina, are associated with the Imperial Court of Kyoto. They can be quite large, though the style lends itself also to small figures. The smiling white face on a big round head appears in many decorative motifs, too, and sometimes in dolls with a different proportion.

7. Daruma dolls represent the Buddhist saint Daruma or Bodhidharma, who according to legend brought Zen enlightenment, and tea, to China and Japan. There are many artistic representations of Daruma as a monk or missionary. According to legend, Daruma sat for years meditating, during which time his arms and legs atrophied, as well as his eyelids (or, alternatively, he tore out his eyelids so as not to fall asleep any more).

7. Daruma dolls represent the Buddhist saint Daruma or Bodhidharma, who according to legend brought Zen enlightenment, and tea, to China and Japan. There are many artistic representations of Daruma as a monk or missionary. According to legend, Daruma sat for years meditating, during which time his arms and legs atrophied, as well as his eyelids (or, alternatively, he tore out his eyelids so as not to fall asleep any more).

The Japanese dolls are paper-maché roly-polys, which one buys with blank eyes so as to paint them in as one accomplishes some task (the first eye when one has formulated the goal, the second eye when it is achieved). This custom may have originated as a thank-offering to the god for good Spring and Fall harvests; if he did not send a good harvest, he would remain blind or one-eyed. These dolls are still performing a significant cultural function, and are purchased particularly at New Year’s, to assist in making resolutions..

There are many related types or versions of Daruma, some of them designated as female–“hime daruma,” or “princess daruma.” One type is made with a gofun face and rich fabrics like a kimekomi ningyo, but shaped like a Daruma; these often come in boy-girl pairs.

8. Hagoita. This is not really a doll, but the padded images on it belong to the construction method of oshie-ningyo, or “padded-painting dolls.” Hagoita, like Daruma, are associated with the New Year. They are richly decorated game paddles, traditionally given as new year’s gifts to girls. The game of hanetsuki is played with a feathered large seed for a shuttlecock and a pair of hagoita. One side is painted, but the other side of the paddle is usually decorated with elaborate padded cloth faces of geisha or kabuki actors.The old year’s paddles are supposed to be burned at the end of the year.