The Tale of Genji (Genji Monogatari) was written around 1000-1025 by a woman known to history as Lady Murasaki or Murasaki Shibiku. We know a bit about her–she kept a diary of her life in the Empress’s court for several years, and we know the positions her father and husband held and her daughter’s name. “Murasaki” is the nickname of her most important female character; it appears that the author herself was referred to by the name of her creation.

Genji is considered the first novel ever written. It is well over 1,000 pages long, 54 chapters; it may or may not be finished. For most of the novel, Prince Genji’s relationships with the women in his life are depicted; around chapter 41, he dies, and the loves of his last wife’s son, Kaoru, become the focus. Genji is the son of an emperor by a minor concubine, and one of his sons becomes emperor and a daughter an empress, so his life is focused on the court in Kyoto; but his love of and skill in contriving painting, writing, poetry, dancing and music, beautiful clothing and gardens, and every refinement of living make him an ideal figure. Connoisseur of the arts and nature, he is also a connoisseur of women, and collects a variety of them; he educates Murasaki from the age of 10 and, when his first wife dies, replaces her with this perfect wife, but he also keeps around him as many women he has loved as possible, whether or not he still desires them or they have reciprocated his desires. Kaoru, on the other hand, is drawn to Buddhist asceticism, and falls in love with a philosopher’s daughter who, like him, resists love as worldly and transient. While the reader of an English translation has the advantage of sorting out the characters by names, in the original most of the characters are not named; the remarkable quality of the characterization is evident if one considers that readers agree on who is speaking or being discussed among all of Genji’s many beloveds. I have drawn up a genealogical table.

The book was illustrated so often through the centuries that there is a genre of painting, Genji-e, “Genji art.”

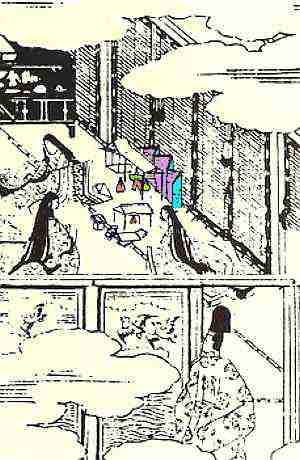

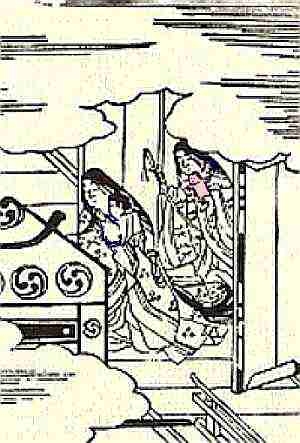

Here are two images from a series of illustrations by Yamamoto Shunso, published first in 1650 and used in Seidensticker’s edition. I have doctored them a bit, adding a little color, to try to bring out the doll images.

Genji, behind a screen, watches Murasaki and two friends playing with dolls. The miniature screens probably function as a doll house (just as the room depicted is framed by screens).

Three or four dolls are depicted, two of them clearly a tachibina pair. Note the shelves at the back of the room, with even more dolls.

Genji’s infant daughter travels to the city with her protective doll. The lady in front carries the child, the lady in back the sword and doll.

Murasaki Shibiku refers to dolls many times in the novel. The following excerpts are taken from the translation by Edward Seidensticker (Knopf, 1976). I do not know the Japanese words used for the various types of ningyo–the play dolls, the child’s totem doll; however, the translator notes the terms used in the last chapters for the type of doll cast into the waves for purification (lustration).

Chapter 5, Lavender (Waka Murasaki)

Genji, travelling in the country, spots the little girl Murasaki and becomes enamored of her. He visits her and discusses his intentions with her grandmother and other protectors. After he has left the region, a relative discusses him with her:

The little girl [Murasaki at 9] too thought him very grand. “Even handsomer than Father,” she said.

“So why don’t you be his little girl?”

She nodded, accepting the offer; and her favorite doll, the one with the finest wardrobe, and the handsomest gentleman in her pictures too were thereupon named “Genji.” (96)

Later, Genji visits Murasaki in the city, where she is mourning her dead grandmother and can’t sleep:

Yes, he had to admit that his behavior must seem odd; but, trying very hard not to frighten her, he talked of things he thought must interest her.

“You must come to my house. I have all sorts of pictures, and there are dolls for you to play with.”

She was less frightened than at first, but she still could not sleep. (104)

Finally, Genji gets Murasaki to his house and begins instructing her in art, writing, and so on.

He ordered dollhouses and as the two of them played together he found himself for the first time neglecting his sorrows. (110)

Chapter 7, An Autumn Excursion (Momiji no Ga)

At this point, though her actual wedding-night is still a few years away, Murasaki’s nurse begins to introduce to Murasaki the idea that Genji will be more to her than a doll-actor in her life:

“And do you feel all grown up, now that a new year has come?” Smiling, radiating youthful charm, Genji looked in upon her. He was on his way to the morning festivities at court.

She had already taken out her dolls and was busy seeing to their needs. All manner of furnishings and accessories were laid out on a yard-high shelf. Dollhouses threatened to overflow the room.

“Inuki knocked everything over chasing out devils last night and broke this.” It was a serious matter. “I’m gluing it.”

“Yes, she really is very clumsy, that Inuki. We’ll ask someone to repair it it for you. but today you must not cry. Crying is the worst way to begin a new year.”

And he went out, his retinue so grand that it overflowed the wide grounds. The women watched from the veranda, the girl with them. She set out a Genji among her dolls and saw him off to court.

“This year you must try to be just a little more grown up,” said Shonagon [her nurse]. “Ten years old, no, even more, and still you play with dolls. It will not do. You have a nice husband, and you must try to calm down and be a little more wifely…. ” A proper shaming was among Shonagon’s methods.

So she had herself a nice husband, thought Murasaki…. The thought came to her now for the first time, evidence that, for all this play with dolls, she was growing up. It sometimes puzzled her women that she should still be such a child. It did not occur to them that she was in fact not yet a wife. (137)

Chapter 12, Suma

Genji has been living in exile in Suma, a wild seacoast area inhabited only by fishermen. A crisis occurs on the third day of the third month (now Momo no Sekku or Hina Matsuri, Girls’ Day). Murasaki does not explain the ceremony, but evidently the casting of a doll or dolls into the sea was assumed to be part of the purification ceremony. We are not told if the doll is made of paper or straw or cloth, and no mention is made of rubbing it on the body for purification before casting it into the sea. In fact, Genji seems to invest too much of himself in this doll:

It was the day of the serpent, the first such day in the Third Month.

“The day when a man who has worries goes down and washes them away,” said one of his men, admirably informed, it would seem, in all the annual observances.

Wishing to have a look at the seashore, Genji set forth. Plain, rough curtains were strung up among the trees, and a soothsayer who was doing the circuit of the province was summoned to perform the lustration.

Genji thought he could see something of himself in the rather large doll being cast off to sea, bearing away sins and tribulations. “Cast away to drift on an alien vastness, I grieve for more than a doll cast out to sea.” (245)

Genji prays in a verse but, as he is standing on the seashore looking so beautiful, the calm sea turns into an appalling storm which rages for days, and which is the King of the Sea’s attempt to claim Genji as a lover.

Chapter 19, A Rack of Cloud (Usugumo)

Genji has arranged for Murasaki to adopt his little daughter by a shy, relatively low-born wife (the Akashi Lady) who does not want to move to the city. The child is still small, about two years old, with short thick hair, “pretty as a doll” (333; see 531, below). The mother agrees to send her to Murasaki.

Only the nurse and a personable young woman called Shosho got into the little girl’s carriage, taking with them the sword Genji had sent to Akashi [where the child was born] and a sacred guardian doll. (334)

Presumably the little girl is still guarded by an Amagatsu, a doll blessed by a Buddhist priest (her grandfather is a Buddhist priest) and given to the mother before the child’s birth; this doll would be destroyed at the ceremony of the “bestowing of the trousers,” at which Murasaki soon presides:

Though no very lavish preparations were made for bestowing the trousers, the ceremony became of its own accord something rather special. The appurtenances and decorations were as if for the finest doll’s house in the world…. (334-35)

Chapter 21, The Maiden (Otome)

Dolls figure in the romance of Yugiri, Genji’s son, and his cousin Kumoinokari, whose father disapproves of the match.

Yugiri continued to think of her, in his boyish way, and was careful to notice her [with a letter] when the flowers and grasses of the passing seasons presented occasions, or when he came upon something for her dollhouses.(366)

Kumoinokari, at the age of perhaps twelve, is described thus:

As she leaned over her koto [stringed instrument] the hair at her forehead and the thick hair flowing over her shoulders seemed to him [her father] very lovely…. As she pushed at the strings with her left hand, she was like a delicately fashioned doll. (367)

Chapter 25, Fireflies (Hotaru)

Genji has Yugiri visit his sister, the Akashi girl adopted in Chapter 19:

The girl was still devoted to her dolls. They made Yugiri think of his own childhood games with Kumoinokari. Sometimes as he waited in earnest attendance upon a doll princess, tears would come to his eyes. (439)

Chapter 28, The Typhoon (Nowaki)

Yugiri visits his father’s house after a terrible storm:

He went to his sister’s rooms.

“She is over in the other wing,” said her nurse….

“It was such an awful storm. I meant to stay with you, but my grandmother was in such a state that I really couldn’t. And how did our dollhouses come through?”

The woman laughed. “Even the breeze from a fan sends her into a terror, and last night we thought the roof would come down on us any minute. The dollhouses required a great deal of battening and shoring.” (465)

Chapter 33, Wisteria Leaves (Fuji no Uraba)

The Akashi lady is reunited after so many years with her daughter, now a future empress:

The girl was like a doll. Gazing on her as if in a dream, the Akashi lady wept, and could not agree with the poet that tears of joy resemble tears of sorrow…. The gods of Sumiyoshi had been good to her. (531: see 333)

Chapter 34, New Herbs (Wakana)

Genji has married a very young, very royal girl, and Murasaki, despite some jealousy, makes friends with her.

Gently, she sought to draw the princess into conversation about illustrated romances and the like. Even at her age, she said, she still played with dolls. She left the princess feeling, in a childish, half-formed way, that this was a kind and gentle lady, not so old in heart and manner as to make a young person feel uncomfortable. (565)

The Akashi Girl has borne a son to the crown prince; Murasaki, as the young mother’s foster mother, enjoys the baby boy, and evidently makes Amagatsu dolls for him as well as toys:

Always fond of children, she made little guardian dolls for the child and more lighthearted playthings, too. She seemed very young as she busied herself seeing to his needs. (572)

Chapter 39, Evening Mist (Yugiri)

Yugiri, married to Kumoinokari, has many children by her; but now he his courting a widow who has sent him a letter, which Kumoinokari has seized and hidden from him.

Persuaded that it was indeed an innocent sort of letter, the busy Kumoinokari had forgotten about it. The children were chasing one another and ministering to their dolls and having their time at reading and calligraphy. The baby had come crawling up and was tugging at her sleeves. She had no thought for the letter. Yugiri could think of nothing else. (689)

Chapter 47, Trefoil Knots (Agemaki)

The ascetic Kaoru has fallen in love with the equally ascetic Oigimi, who has not yielded to him and is dying of despair, self-starvation, and loneliness after her father’s death.

She became more sadly beautiful the longer he gazed at her, and the more difficult to relinquish. Though her hands and arms were as thin as shadows, the fair skin was still smooth. The bedclothes had been pushed aside. In soft white robes, she was so fragile a figure that one might have taken her for a doll whose voluminous clothes hid the absence of a body. Her hair, not so thick as to be a nuisance, flowed down over her pillow, the luster as it had always been. Must such beauty pass, quite leave the world? (865)

Chapter 49, The Ivy (Yadorigi)

The image of a doll cast away on a river runs through the story of Ukifune in the last few chapters of the book.

Kaoru is still mourning Oigimi (older sister) and confides in Nakanokimi (younger sister), now his best friend Prince Niou’s wife. She teases him by implying he wishes to float a doll, made in the image of her sister, down a river as purification. He has implied that he would literally worship such an image.

“An end to sorrow,” he whispered. “No, it is too much. Let me have a Silencetown somewhere, a place for quiet tears. Somewhere near that monastery of yours. No, I don’t need a whole monastery. If I could just have a statue [hitokata] or a picture of her, and set out offerings before it.”

“A very kind thought. But just a moment–you speak of having an image made, and that somehow suggests the river Mitarashi. And so perhaps you are not being kind to my sister after all. Or a picture: much depends, you know, on what you are willing to pay. An artist can do very badly by a person.” (915-16)

Note from E. Seidensticker, the translator: Kaoru has used the word hitokata, which suggests the images floated down rivers during lustration ceremonies. Mitarashi can have general reference to any stream so used, or specific reference to the stream flowing throught he precincts of the Lower Kamo Shrine in Kyoto.

Chapter 50, The Eastern Cottage (Azumaya)

Nakanokimi has found a half-sister (Ukifune) who resembles Oigimi, and she refers back to the earlier conversation to let Kaoru know about this addition to her household. They exchange verses using the imagery of purification dolls.

…she had presently to recognize the genuineness of his sorrow. She sighed. Then, perhaps hoping to wash away part of the pain, she mentioned the “image” of which they had spoken. An image had come in secret to this very house, she let it be known.

This was exciting news. He longed to be shown to the girl’s presence, but feared that he might seem capricious.

“It would indeed be a comfort if an idol were to come at my command. But a bad conscience would only muddy the waters.”

“It is not easy to be a saint.”…

“But you might at least describe my feelings to them…. The permanent loan, if you please, of a useful image [nademono], a handy memento, to take away the gloom.”

“To float downstream afresh at each atonement, and yet to have forever at your side? No, there are too many hands tugging at you. I would fear for the poor girl.”

“You know very well which shoal I shall come upon in the end…. I am like the foam that sinks and rises again, and I find your talk of being floated downstream very much to the point.” (930-31)

Note from Seidensticker: The image is of nademono, dolls to which, during lustration ceremonies, impurities and afflictions were transferred by bodily contact. They were then cast away down a stream. “Too many hands are tugging at the nusa; my love it may command, but not my faith.”

Chapter 51, A Boat Upon the Waters (Ukifune)

Ukifune has become the mistress both of Kaoru and of Prince Niou. In the complex emotions of love and guilt at betraying both Kaoru and Nakanokimi–and herself–by desiring Niou, she contemplates drowning herself.

Yes, it was a terrible river, swift and treacherous, said one of the women. “Why, just the other day the ferryman’s little grandson slipped on his oar and fell in….”

If she herself were to disappear, thought Ukifune, people would grieve for a while, but only for a time; and if she were to live on, an object of ridicule, there would be no end to her woes….

They must arrange for invocations to the Blessed One, said [Ukifune’s mother]… and there must be lustrations and propitiatory rites to the native gods as well.

She rambled on, quite unaware of what these “lustrations” of hers might mean to her daughter, of the stain the girl would want to wash away in the river Mitarashi. (999)

Chapter 52, The Drake Fly (Kagero)

Kaoru reflects on Ukifume’s fate after she appears to have drowned herself:

How sinister his ties had been with this river, how deep its hostility flowed!…There had been bad omens, he now saw, from the start: in that “image,” for instance, of which Nakanokimi had first spoken, an image to float down a river.