I’ve just returned from the inaugural Poetry by the Sea conference–a gathering of contemporary poets as diverse as Rafael Campo, Annie Finch, Marilyn Hacker, Spencer Reece, Patricia Smith, and A. E. Stallings. Held at Mercy by the Sea in Madison CT (a Catholic spiritual retreat and conference center), the event offered spaces for camaraderie, contemplation, and creativity.

I’ve just returned from the inaugural Poetry by the Sea conference–a gathering of contemporary poets as diverse as Rafael Campo, Annie Finch, Marilyn Hacker, Spencer Reece, Patricia Smith, and A. E. Stallings. Held at Mercy by the Sea in Madison CT (a Catholic spiritual retreat and conference center), the event offered spaces for camaraderie, contemplation, and creativity.

Enter. The seaside Labyrinth Garden was one of my favorite spaces, and so my account of a conference committed to form offers a labyrinth walk through Poetry by the Sea. Like artful poems, labyrinths offer unexpected turns and returns that guide participants through an intricate pattern. We traverse it with our feet.

Turn 1. I entered this labyrinth through knowing its founder and director, Kim  Bridgford; we studied modern poetry at the University of Illinois as grad school mates. I wrote my dissertation on W. H. Auden and documentary film. She wrote hers on five American women poets, and now edits the journal Mezzo Cammin (devoted to formalist poetry by women). I did not know then that I’d take another turn, following Kim into the field of women’s poetry studies. She was how I found out about Muriel Rukeyser. This week I read the opening sonnet sequence to Kim’s new volume Doll on the Mercy Center beach. And my co-authored conference talk featured Rukeyser.

Bridgford; we studied modern poetry at the University of Illinois as grad school mates. I wrote my dissertation on W. H. Auden and documentary film. She wrote hers on five American women poets, and now edits the journal Mezzo Cammin (devoted to formalist poetry by women). I did not know then that I’d take another turn, following Kim into the field of women’s poetry studies. She was how I found out about Muriel Rukeyser. This week I read the opening sonnet sequence to Kim’s new volume Doll on the Mercy Center beach. And my co-authored conference talk featured Rukeyser.

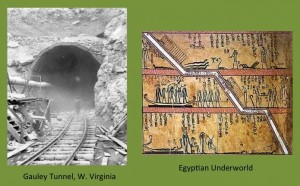

Turn 2. My frequent collaborator Mary Ann Eaverly (UF Classics) and I spoke about modern women poets writing ancient Egypt: Rukeyser, H.D., and Ágnes Nemes Nagy (a Hungarian  poet). This slide from our talk links Gauley Tunnel, West Virginia (the key site of Rukeyser’s documentary poem The Book of the Dead) with the entrance to the Egyptian Underworld. Rukeyser had contemplated the ancient Book of the Dead, which she saw at the British Museum. At the conference, Mary Ann and I were scholars surrounded by creative writers: we loved the change of pace.

poet). This slide from our talk links Gauley Tunnel, West Virginia (the key site of Rukeyser’s documentary poem The Book of the Dead) with the entrance to the Egyptian Underworld. Rukeyser had contemplated the ancient Book of the Dead, which she saw at the British Museum. At the conference, Mary Ann and I were scholars surrounded by creative writers: we loved the change of pace.

Turn 3. In The Life of Poetry, Rukeyser mentions the influence of the British documentary film movement, which incorporated Auden poems in its productions Coal Face and Night Mail. (You can see the latter here.) Two conference events I attended had documentary connections.

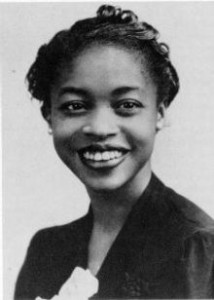

Turn 4. In his talk for the Margaret Walker Centenary panel (chaired by Cherise A. Pollard), David A. Taylor mentioned the film based on his book Soul of a People: Writing America’s Story, a chronicle of the Federal Writers’ Project during the Great Depression. Walker worked in the FWP’s Chicago Office before writing For My People (1942), which garnered the Yale Younger Poets Award. She was the first African American to receive it.

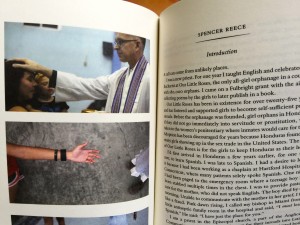

Turn 5. I also attended the screening of the film-in-progress Our Little Roses, a documentary based on Spencer Reece’s recent experience leading poetry workshops at an orphanage for girls in Honduras. Reece gave out copies of the January 2015 issue of Poetry magazine that includes a cluster of the girls’ poems and film stills. (You can watch a teaser for the film here.) Reece appears in the upper image on the left page; he is an Episcopal priest as well as a poet.

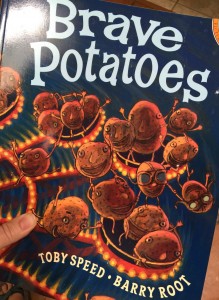

Turn 6. The Children’s Poetry panel I attended included a senior editor at Highlights magazine, Joëlle Dujardin. Poet and writer Toby Speed (author of Brave Potatoes) offered strategies for writing poems for children. She encouraged us to tap childhood rhythms of nursery rhymes, “loved poems,” jump rope rhymes, and other “chanting games” such as Red Light, Green Light. Revisiting childhood books can unlock these memories. I remember my delight at finding an illustrated Jason and the Argonauts in my elementary school library. It was my first exposure to Greek mythology.

Turn 6. The Children’s Poetry panel I attended included a senior editor at Highlights magazine, Joëlle Dujardin. Poet and writer Toby Speed (author of Brave Potatoes) offered strategies for writing poems for children. She encouraged us to tap childhood rhythms of nursery rhymes, “loved poems,” jump rope rhymes, and other “chanting games” such as Red Light, Green Light. Revisiting childhood books can unlock these memories. I remember my delight at finding an illustrated Jason and the Argonauts in my elementary school library. It was my first exposure to Greek mythology.

Turn 7. Another book I picked up at the conference is A. E. Stallings’s latest volume Olives, which she dedicates “for my Argonauts.” Its third section is “Three Poems for Psyche,” and one of the new poems she read is about Pandora. Mary Ann and I just taught Stallings’s poems about Eurydice and Penelope in our team-taught course, “Women Writers and Classical Myths.” We had a chance to chat at breakfast on the last day of Poetry by the Sea. Like Reece, Stallings taught a workshop as one of the conference’s faculty.

Turn 7. Another book I picked up at the conference is A. E. Stallings’s latest volume Olives, which she dedicates “for my Argonauts.” Its third section is “Three Poems for Psyche,” and one of the new poems she read is about Pandora. Mary Ann and I just taught Stallings’s poems about Eurydice and Penelope in our team-taught course, “Women Writers and Classical Myths.” We had a chance to chat at breakfast on the last day of Poetry by the Sea. Like Reece, Stallings taught a workshop as one of the conference’s faculty.

Exit. Labyrinths are mythic spaces that allow us to elude our minotaurs. Labyrinths are spiritual spaces that allow us to thread our thoughts through form.

“Till by turning, turning we come round right.” (Joseph Brackett, “Simple Gifts”)

“In my end is my beginning.” (T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets)