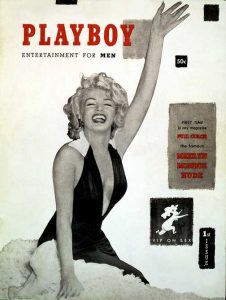

With Hugh Hefner’s passing, the sexual revolutions of the 1950s and 60s are trending again in the news. The fundamental revolution of Playboy wasn’t its nude female models, but its new model of masculinity. Following in the wake of Alfred Kinsey’s 1948 sensation, Sexuality in the Human Male, Hefner’s magazine was one of several that called out to American men who didn’t fit the standard models. In a decade of Cold Warriors, Beatniks, Suburban Dads, and Organization Men, what else could a man be? William Segal’s Gentry magazine highlighted the national crisis of masculinity in 1951 with its debut feature “What Does It Mean to Be a Man?” Pushing back against 3-M masculinity (medals, money, muscles), Gentry fashioned a Dandy identity for wealthy American men who wanted Cubism with their cravats and Goethe with their gabardine. The jet-setting Gentry man sported bold colors in his evening wear, collected art, enjoyed shopping, and thrived on cultured conversation. Like Esquire, which debuted in 1933, Gentry appealed to upscale male consumers of culture and style. Though home decor greatly interested such men, they were not ‘domestic’ when they were home–their place of leisure rather than labor. Hefner’s magazine was and was not an outlier in this wider context.

With Hugh Hefner’s passing, the sexual revolutions of the 1950s and 60s are trending again in the news. The fundamental revolution of Playboy wasn’t its nude female models, but its new model of masculinity. Following in the wake of Alfred Kinsey’s 1948 sensation, Sexuality in the Human Male, Hefner’s magazine was one of several that called out to American men who didn’t fit the standard models. In a decade of Cold Warriors, Beatniks, Suburban Dads, and Organization Men, what else could a man be? William Segal’s Gentry magazine highlighted the national crisis of masculinity in 1951 with its debut feature “What Does It Mean to Be a Man?” Pushing back against 3-M masculinity (medals, money, muscles), Gentry fashioned a Dandy identity for wealthy American men who wanted Cubism with their cravats and Goethe with their gabardine. The jet-setting Gentry man sported bold colors in his evening wear, collected art, enjoyed shopping, and thrived on cultured conversation. Like Esquire, which debuted in 1933, Gentry appealed to upscale male consumers of culture and style. Though home decor greatly interested such men, they were not ‘domestic’ when they were home–their place of leisure rather than labor. Hefner’s magazine was and was not an outlier in this wider context.

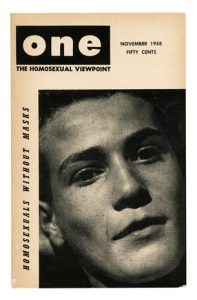

Playboy and its revolutions in masculinity emerged in 1953, the same year The Mattachine Society’s One magazine offered

Playboy and its revolutions in masculinity emerged in 1953, the same year The Mattachine Society’s One magazine offered  gay men travel advice, literary reviews, social analysis, and advocacy. Hefner’s magazine assured middle-class, straight men “there was nothing queer” about artiness and “indoor pleasures,” as Barbara Ehrenreich puts it. Hefner created a new brand of American bachelors in his first editorial: “We enjoy mixing up cocktails and an hors d’oeuvre or two, putting a little mood music on the phonograph, and inviting in a female for a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.” This fabled Playboy preamble jabs at the more refined masculinity in Segal’s publication, working in tandem with the Mattachine Society’s magazine to bring male sexuality out into the open. All of these magazines offered alternatives to mainstream masculinity. Some of them required the company of women to enact, and some did not. They all rejected suburbia. Playboy, One, and Gentry offered DIY identity kits that reclaimed indoor spaces for manly pursuits. Hefner’s passing reminds us that American masculinity never was (and never well be) a one-size-fits all identity -MB

gay men travel advice, literary reviews, social analysis, and advocacy. Hefner’s magazine assured middle-class, straight men “there was nothing queer” about artiness and “indoor pleasures,” as Barbara Ehrenreich puts it. Hefner created a new brand of American bachelors in his first editorial: “We enjoy mixing up cocktails and an hors d’oeuvre or two, putting a little mood music on the phonograph, and inviting in a female for a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.” This fabled Playboy preamble jabs at the more refined masculinity in Segal’s publication, working in tandem with the Mattachine Society’s magazine to bring male sexuality out into the open. All of these magazines offered alternatives to mainstream masculinity. Some of them required the company of women to enact, and some did not. They all rejected suburbia. Playboy, One, and Gentry offered DIY identity kits that reclaimed indoor spaces for manly pursuits. Hefner’s passing reminds us that American masculinity never was (and never well be) a one-size-fits all identity -MB

References:

Editorial attributed to Hugh Hefner. Playboy (January 1953).

Ehrenreich, Barbara. The Hearts of Men: American Dreams and the Flight from Commitment. 1983.

MB, “Gentry Modernism: Cultural Connoisseurship and Midcentury Masculinity, 1951-57,” forthcoming in Popular Modernism and Its Legacies, ed. Scott Ortolano.