I’ve taught Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar many times in several courses: American literature, major authors, women’s literature, and the American 1950s. Most are brimming with English majors. During my class discussions in the late 1990s, a few students would identify with protagonist Esther Greenwood’s mental health struggles. By the time I was teaching the novel to older Millennials, a sizable group of students was finding Esther’s academic performance anxiety parallel to their own. Theirs was the first test-test-test generation: scores on an expanded array of standardized tests would affect public K-12 school funding. Esther sweated her grades to maintain her scholarship at an elite private college. My students fretted over feeling responsible if a teacher got terminated because of their school’s test scores. I sensed that Plath’s most famous character was becoming more mainstream.

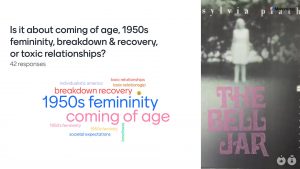

This year I taught The Bell Jar to General Education students for the first time; most were freshmen and none were Humanities majors. A few had heard of Sylvia Plath, yet none seemed to have read her writing. The course was on the American 1950s and campus life, featuring literature by Plath, John Cheever, Gwendolyn Brooks, Flannery O’Connor, James Baldwin, and Sloan Wilson. We also watched Fifties family sitcoms and Rebel Without a Cause. For parsing postwar campus life, we did a deep dive into student publications in our University Archives. The weeks on Plath were my first in which students didn’t bring up the writer’s life. They were more interested in Esther’s campus life–finding much of her story highly relevant to their own. For them The Bell Jar was primarily a coming-of-age story, as well as a story about 1950s gender roles for women. Very few students thought it centered on breakdown and recovery–a consensus view from their Millennial predecessors. Mental illness and mental healthcare are everyday things now, and Plath’s protagonist strikes them as more normative than outlier. People are marrying later, and more of my students come from two-career households.

In their final papers on how their lives would change if they attended college in the 1950s, several students wrote that they couldn’t help but see themselves in Esther Greenwood–whether or not their gender, race, or ethnicity matched hers. My hunch is that these factors have brought about Bell Jar Z.0:

Fear of Failure. Being over-tested surely highlighted the fear of failure my students see in Esther–and sometimes in themselves. When I was in high school in the 1970s, I didn’t have the pressures of getting top grades to qualify for a free state tuition deal. I did feel a responsibility to do well because of my parents’ investment in my college education. But a high GPA wouldn’t save them money. In The Bell Jar, Esther felt the pressures of a practically perfect opportunity: a private school scholarship + a top summer internship in New York. She also bore the burden of her mother’s palpable disappointment in her setbacks.

Isolation and Expectations. Like all my recent students, this year’s GenEd students were isolated during a formative period of their education, separated from their peers and support networks through remote pandemic learning. For GenZ this happened during middle and/or high school. Several students’ papers mentioned how Esther’s isolation as an aspiring young woman and a newcomer to city prompted them to consider how they would be isolated as 1950s college students–as the only members of their demographic in their classes or majors, as first-generation college students, as international students. They can relate to the suffocation of circumstances and social expectations. I was struck by one student’s response that The Bell Jar was fundamentally about loneliness.

Fig Trees, FOMO & Futures. Most of these students saw themselves in Esther’s fig tree analogy: picking the fruit from one branch meant foregoing the others. They could identify with the paralysis of indecision that could leave them with an empty tree and unfulfilled ambitions. While the term FOMO (fear of missing out) was coined a decade ago, it started spreading through social media in 2010–when GenZ was coming of age. Facing more migratory job markets and anticipating more career changes than their predecessors, this generation is moving beyond binary models of career paths as they embrace less binary models of gender roles. Instead of regretting roads not taken, they tend to envision more than one future for themselves.

Unmoored from the facts of (and fixations on) Plath’s life, more GenZ students are beginning to make her novel their own story. Sixty years after its publication, The Bell Jar may be finding the wider audience it has waited for all along. – MB

Student work used by permission.