The Humanities have become a sustainability study in these STEM-driven times for higher education. How does our hive survive the academic climate changes of a shrinking professoriate, curricular compression, and a nomadic job market? How do Humanities workers maneuver within and across our smaller footprints at public institutions? My Spring course took into account these changes. I designed “Modernist Studies & Pedagogy Workshop” for graduate students in our PhD and MFA programs. In choosing materials, I took into account my students’ diverse interests and career paths. These initial findings are preparatory material for a design review.

The Humanities have become a sustainability study in these STEM-driven times for higher education. How does our hive survive the academic climate changes of a shrinking professoriate, curricular compression, and a nomadic job market? How do Humanities workers maneuver within and across our smaller footprints at public institutions? My Spring course took into account these changes. I designed “Modernist Studies & Pedagogy Workshop” for graduate students in our PhD and MFA programs. In choosing materials, I took into account my students’ diverse interests and career paths. These initial findings are preparatory material for a design review.

Sustainable Pedagogy is Resourceful. Materials-driven, my seminar incorporated modernist literary, critical, and visual texts; short essays about teaching; resources from our campus museum and library; teaching and conference materials I’ve made; materials from conference colleagues. I included teaching materials from other graduate students and from colleagues in English, Art History, Architecture, the Harn Museum of Art, and UF Libraries. My students worked with these shared resources, and they shared each other’s work. We practiced a renewable resourcefulness.

Sustainable Pedagogy is Cross-Campus. Partnerships I have formed across campus proved as crucial as my expertise in designing my seminar. The campus became our campus unit. We ventured across three colleges: Liberal Arts & Sciences; Arts; and Design, Construction & Planning. Interdisciplinary work requires physically crossing over to our colleagues in other disciplines and consulting with them. Through conversations we discovered that we were teaching some of the same materials.

Sustainable Pedagogy is Collaborative. Within our seminar room my students workshopped Beta assignments for future students and draft instructional resources for our campus museum. As the seminar emerged through our texts and campus partnerships, we became a pedagogy ensemble. We offered a roundtable presentation on teaching close reading for our department’s graduate organization. We visited an Art History class before we team-taught it. We were team taught by an undergraduate architecture class.

Sustainable Pedagogy is Creative. Much of our seminar work involved making instructional materials, generated from broad keywords that did not constrain our thinking. For example: Write an actual assignment about Cities that you would give your own students in a college-level course (or type) of your choice. Think of your Assignments as prototypes or Beta assignments. The idea is to generate materials that we can workshop, refine, and use. Connect your assignment to at least one primary text on our syllabus. This was the most creative work many students had done in a seminar.

Sustainable Pedagogy is Ethical. All teaching materials were shared by permission within and beyond my seminar. Our cross-campus consulting proceeded by outreach and invitation. Where possible, we offered resources in exchange for those we received. We shared our resources; we made new resources; I offered to visit my colleagues’ future courses. Through such ethical practices, Humanities workers sustain one another.

Sustainable Pedagogy is Beyond-the-Book. I have taught and benefitted from book-oriented seminars. Yet if Humanities departments are now envisioning beyond-the-book dissertations, shouldn’t seminar design take this into account? My seminar did not conform to the standard production line: seminar paper > journal article > dissertation > book. Using modular forms, my seminar assignments were outward-facing toward classrooms, conferences, journals, museums, and the public. Such assignments are resourceful for jobs within and beyond the academic market.

Sustainable Pedagogy is Repurposing. I tell all of my graduate students that everything they write or make in their coursework should have at least one afterlife. My debut pedagogy seminar-workshop practiced repurposing, opening new synergies between our academic writing and our teaching. We can repurpose our student assignments into blog posts, conference papers, publications, and museum guides. We can transpose academic writing into crossover writing. We can transport a module from something we’ve made to something we are now making.

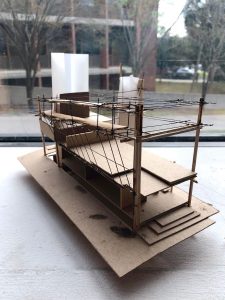

(re)Source

I took this photo in the Architecture Teaching Gallery on Feb. 12. There was no label, so I cannot credit this model’s maker. Resourceful in its available materials (wire, wood, paper), the design offers an inventive prototype. The stained plywood marks the material’s prior states as it supports a new geometric form. A fitting figure for the work of sustainable pedagogy. –MB

- I wrote this post at the 2019 Humanities Writing Retreat, sponsored by UF’s Center for the Humanities and the Public Sphere.