Imagine arranging your students in vertical rather than horizontal space. Imagine them traversing the tower stairs in iambic rhythm, working the meter into muscle memory. Imagine composing a carillon piece from sonnet forms, and parsing sonnet forms through musical notation. Crossing artistic media–and crossing the street from our classroom building to UF’s Century Tower–my Modern British Poetry class recently embarked on a Sonnet Ascent with carillonneur-composer Mitchell Stecker, a graduate student in Musicology. You might say we took poetry from the ivory tower to the bell tower.

Proposition A: Inviting poetry survey students to become sonneteers expands the experience of reading formal poems. This is an especially effective pedagogy for British poetry because modern British poets tended to stay in form more often than their American counterparts. (The sonneteers on our syllabus are W. B. Yeats, Wilfred Owen, W. H. Auden, Philip Larkin, and Carol Ann Duffy.)

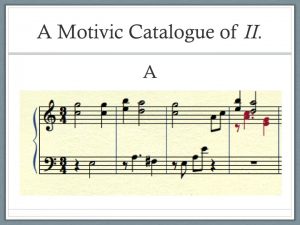

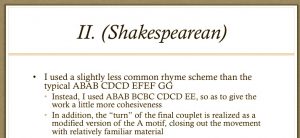

Proposition B: Generating a musical composition from traditional sonnet forms expands the possibilities for sequencing 21st century music. The aim is not to set a poem, but to transpose a poetic structure into a musical one. The challenge for this carillon piece is to avoid monotony, as the musical equivalent of rhymed words would be repeated notes. How to rethink sonic repetition in patterned forms?

Proposition C: Hearing a musician talk about the creative process of working with sonnet forms can inspire poetry students with their sonnet-making.

Proposition D: Constraint does not close off creative expression.

Sonneteering and sonatinas. My students had already acquired sonnet-

Sonneteering and sonatinas. My students had already acquired sonnet- making gear in the form of technical resource sheets. Now they needed to think about form itself in an unexpected way. Why would someone write new music based on old literary forms? Did the constraint present obstacles or limitations?

making gear in the form of technical resource sheets. Now they needed to think about form itself in an unexpected way. Why would someone write new music based on old literary forms? Did the constraint present obstacles or limitations?

On Sonnet Ascent day, we warmed up by marching in place as students spoke in impromptu iambic rhythm when I pointed to them. Stecker then discussed his carillon composition in our classroom, focusing on the Shakespearean sonnet movement he would play for us in Century Tower. (The other movements are based on Dantean and Petrarchan sonnet structures.) Here are excerpts from Stecker’s slides. Students asked him questions about his creative process, the layout of the carillon clavier, and how one plays the instrument. We all made an expedition to Century Tower, learning more about UF’s carillon and exploring the soundscapes we made in the 11-flight stairwell. (Later, I recalled the 11-line English stanza form called the roundel.) At the top of the tower, Stecker debuted his composition for my students.

After making their Sonnet Ascent, my students have gained their rhythmic feet. I look forward to hearing them perform their summer sonnets on our last day of Modern British Poetry.

Never had I more

Excited, passionate, fantastical

Imagination, nor an ear and eye

That more expected the impossible

— W. B. Yeats, “The Tower” (1927)

Sources:

Digitized Polaroid photos by Joselliam Urbina.

Lecture slides by Mitchell Stecker.

W. B. Yeats, Selected Poems and Three Plays.

All recognizable people pictured gave permission for this post.

*The linked YouTube video is Benjamin Britten’s setting of Wilfred Owen’s Shakespearian sonnet “Anthem for Doomed Youth,” from War Requiem (1962).

–MB