Something closed must retain our memories, while leaving them their original value as images. –Gaston Bachelard

Something closed must retain our memories, while leaving them their original value as images. –Gaston Bachelard

In his meditative book The Poetics of Space, philosopher-poet-postmaster Gaston Bachelard situates the house within a series of concentric circles. Our houses radiate outward from the psyche to the sidewalk, from early memory to later recollection, from childhood daydreaming to future architectures. For Bachelard the space of the home holds an ultimate poetic depth that we can fathom only through dreams, memories, and poems. As we continually reconstruct our houses through images and words, our preoccupations with space become reoccupations of generative spaces.

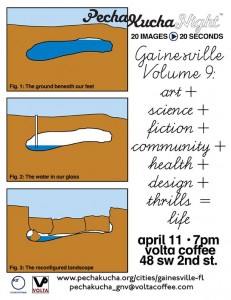

(Once at Volta, I did a presentation with 20 images. I heard several poetry and fiction readings there.)

All really inhabited space bears the essence of the notion of home.

A coffeehouse is a community space where we can daydream, read, and write alone in company, or we might converse with persons already known or previously unknown. Each coffeehouse creates transient soundscapes of that moment’s music from the speakers, the varied rhythms of surrounding conversations and their languages, the intermittent keyboard clicks I’m making in this space at this moment.

Hanging from the ceiling across from me is a wooden sculpture that lets in the light between its sticklike components—as if someone pried open an  architectural model. A house suspended in air. Cradled within an interstice lies a small mass of more densely assembled material; it resembles a bird’s nest. The surrounding coffeehouse nests its various assemblages of patrons with open spaces between the hard, smooth surfaces of its counters and shelves, tables and chairs.

architectural model. A house suspended in air. Cradled within an interstice lies a small mass of more densely assembled material; it resembles a bird’s nest. The surrounding coffeehouse nests its various assemblages of patrons with open spaces between the hard, smooth surfaces of its counters and shelves, tables and chairs.

For our house is our corner of the world.

My coffeehouse has two floor-to-ceiling windows on its outer wall; each has four panels. Through these windows the interior space is sculpted with natural light: the skyscape of bright or mottled clouds, the clarifying light of cloudless days. These windows also bring the downtown streetscape into an almost tactile proximity. Lines of mortar portion out the individual bricks, abrasions add texture to the asphalt, weathered concrete curbs divide them.

A house constitutes a body of images that give mankind proofs or illusions of stability.

A coffeehouse is the opposite of one’s workplace or home office, an altogether different kind of space than a reading nook at a school or library. It is an alternative home that is more open to the spaces around it. A poetic space that houses a transient togetherness, a transit house that posts its memories forward. A coffeehouse shelters rootlessness and fosters dreams. – MB

Volta closed its doors on May 27, 2024.

Sources:

- Feature image by Anthony Rue, co-founder of Volta Coffee, Tea & Chocolate, 48 SW 2nd St, Gainesville, FL. January 2, 2013.

- Auxiliary images by MB. May 26, 2024.

- All italicized quotations are from Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space (1958), selected as personal takeaways by a former community of students and by Charlie Hailey for his Architecture classes.