Shelley famously declared that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” I find that women poets are often community organizers in the literary world. The collective that formed Kalliope (1978-2005), an internationally acknowledged journal of women’s literature and art, has ties to my local community of North Central Florida. The journal was published at Florida Community College at Jacksonville (FCCJ), and long-serving editor Mary Sue Koeppel’s papers are housed here at UF. Appearing in its pages were emergent writers alongside such established figures as Maxine Kumin, Denise Levertov, Joy Harjo, and Naomi Shihab Nye. Kalliope also interviewed Margaret Atwood, Gwendolyn Brooks, June Jordan, Iris Murdoch, and Alice Walker. Koeppel explains that these women’s insights to the writing process “might serve as models or inspirations for others” (1). In addition, the journal published translations of Colette and Marina Tsvetaeva.

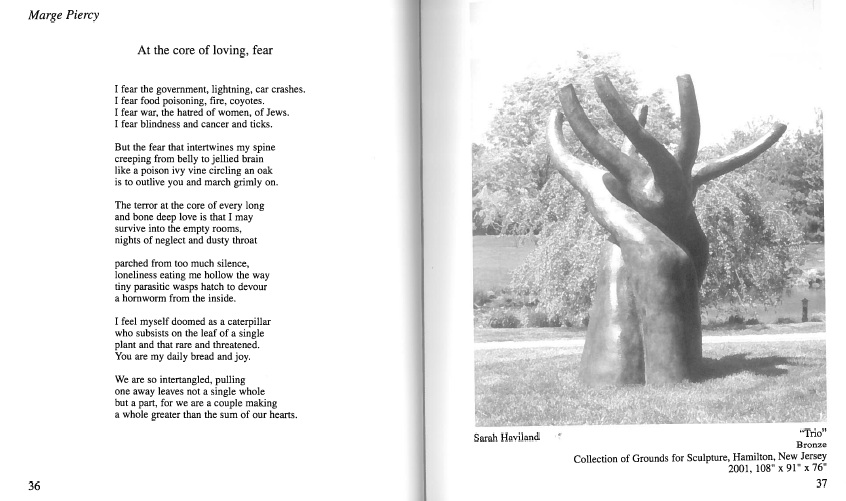

Reproductions of women’s photography, paintings, sculpture, and woodcuts also filled the journal’s glossy pages, shaping what I call the image-text of women’s poetry studies (2). As we see from this page pairing in the 25th Anniversary issue–a poem by Marge Piercy and a bronze sculpture by Sarah Haviland—Kalliope’s layout reminds us that visual culture offers more dynamic contexts for women’s writing than the nudes and Madonnas of art history. Piercy, Kumin, and Harjo were key Muses for the Kalliope collective, supporting the journal and its community projects. Harjo also inspired the journal’s volume of poems geared toward children, Lollipops Lizards & Literature (1994).

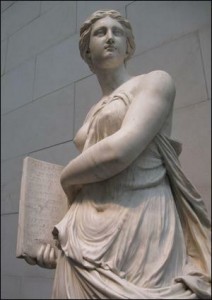

The journal’s namesake, Kalliope (also Calliope), was the ancient Greeks’ Muse of epic poetry–traditionally the most elevated mode of Western poetry since Homer. Founding editor Peggy Friedmann explained the Kalliope collective’s epic task in her introduction to the Tenth Anniversary Issue, noting the great difficulty women writers had getting their work published in the reigning literary journals of the late 1970s. (The journal received 8070 literary submissions in 2001.) The journal’s namesake also appeared in the quote from Anne Bradstreet printed in each issue. It begins “I am obnoxious to each carping tongue / Who says my hand a needle better fits,” and ends with these lines:

The journal’s namesake, Kalliope (also Calliope), was the ancient Greeks’ Muse of epic poetry–traditionally the most elevated mode of Western poetry since Homer. Founding editor Peggy Friedmann explained the Kalliope collective’s epic task in her introduction to the Tenth Anniversary Issue, noting the great difficulty women writers had getting their work published in the reigning literary journals of the late 1970s. (The journal received 8070 literary submissions in 2001.) The journal’s namesake also appeared in the quote from Anne Bradstreet printed in each issue. It begins “I am obnoxious to each carping tongue / Who says my hand a needle better fits,” and ends with these lines:

But sure the antique Greeks were far more mild

Else of our sex, why feigned they those nine

And poesy made Calliope’s own child…

Along with Calyx (founded in 1976), Kalliope offered women new opportunities to get their work into print, drawing submissions from around the world. Friedman noted that by 1988 women writers’ “epic journey” was “not over, certainly, but the road is becoming a little smoother” (3). In our own cultural moment of The VIDA count, we can say that the journey of women’s writing is ongoing. Like VIDA, headed by Cate Marvin and Erin Belieu, Kalliope began with women poets’ vital work as community organizers. As Koeppel explained to me recently, “the inability of the world to support women made us choose ourselves for this mission” (4). As Muses and organizers, questioners and questers, women poets acknowledge the need for more legislators in a more diverse literary world. –MB

(1) Mary Sue Koeppel, “Kalliope at 20: A Brief History,” 20.3, 1998.

(2) See the closing Manifesto to Women’s Poetry and Popular Culture, 2013.

(3) Peggy Friedmann, “Kalliope: The First Ten Years” 10.3, 1988.

(4) Interview, July 2014.