Today I wrapped my graduate seminar Women’s Writing & Pedagogy with a reveal of students’ Domestic Arts Assemblage projects, crafted from discarded items at our community’s creative reuse center, The Repurpose Project. This is a debut DIY assignment I designed specifically for this course, which combines a seminar on 20th/21st century women’s literature with a practical workshop on assignment mock-ups students design for courses they might teach in future.

Over the past 3.5 months we’ve read women’s writing in various forms: novels, experimental prose, poems, and image-texts. Our writers/makers: Sylvia Plath, Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf, Stevie Smith, Gwendolyn Brooks, Angela Carter, Alison Bechdel, Rita Dove, Margaret Atwood, and Ange Mlinko. We also explored our library’s archive of Kalliope: A Journal of Women’s Literature and Art. Keyed to this range of women’s literary writing in English, the series of assignment mock-ups focused on: City, Domesticity, Literary Magazine, Myth. Students also did other short assignments, including a conference paper proposal about teaching and a draft syllabus that featured women’s writing.

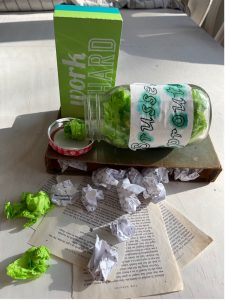

The Domestic Arts Assemblage is the outlier assignment. My rules were loose, resourceful, and communal:

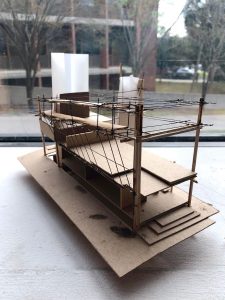

(1) Make a Domestic Arts Assemblage with items from The Repurpose Project. MB will give you $8.00 to use for your project. At least one of our syllabus texts or a mock-up assignment should be a source of inspiration.

(2) Submit a photo of your Domestic Arts Assemblage + a 250-300 word Maker Statement.

By doing a creative-critical assignment, students could curate syllabus materials alongside everyday objects to reflect on our semester’s discussions and generate ideas for future work.

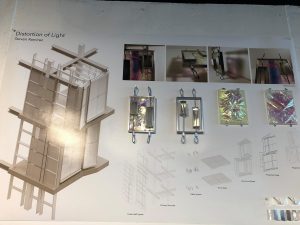

The resulting assemblages were stunning, as you can see from the writing-themed examples I’m sharing here (with students’ permission). Viewing the projects as a gallery and discussing them with their makers in today’s class, I was struck by how they reassembled our syllabus and discussions in analytical and inventive fashion. This teacher became the student, learning new pedagogies. Here are some of my takeaways:

- Women’s writing can be laden with everyday objects, bringing texture and heft to the words.

- Domestic Arts Assemblage makes us question why we label some work as domestic, and some work as art.

- The domesticity in women’s writing covers some things while revealing others.

- In women’s writing, the women characters can succumb to and liberate themselves from the cycles of time.

- In women’s writing, domestic objects can signify burdens and rebirth, fragmentation and integration, restriction and possibility.

- The household objects we donate or otherwise discard are inanimate narrators of our everyday lives. – MB