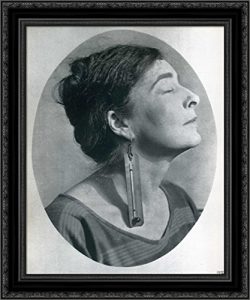

Maker of poems, paintings and assemblages, designer of household objects, Mina Loy is a fitting figure to bring into my seminar Modernist Studies & Pedagogy. Her creations are magnets of modernity. And their futuristic forays anticipate Digital Humanities, fueling DH projects such as Mina Loy: Navigating the Avant-Garde. Mina Loy is not the poster woman of modernist studies; she is its digital platform.

Maker of poems, paintings and assemblages, designer of household objects, Mina Loy is a fitting figure to bring into my seminar Modernist Studies & Pedagogy. Her creations are magnets of modernity. And their futuristic forays anticipate Digital Humanities, fueling DH projects such as Mina Loy: Navigating the Avant-Garde. Mina Loy is not the poster woman of modernist studies; she is its digital platform.

And so I choose this blog post for my seminar postscript to Loy’s 34-poem sequence “Songs to Joannes.” The Loy Chronology on MAPS informs us that the first four poems first appeared in Others: A Magazine of New Verse (1915); the full sequence appeared in the magazine in 1917. The titular “Joannes” is code for Giovanni Papini, one of Loy’s fraught relationships and Futurist forays. Think of my Five Things as a handful of cards. Play them as you like.

- Anti-Romantic Love Poems. The poem’s title is a wild card. If someone composes songs for a first-name basis someone, we might expect rhapsodic tributes to a lover or beloved friend. When Poem 1 plays its Cupid image, we don’t expect a Pig Cupid…Rooting in erotic garbage. Instead of romantic transcendence, these poems are rooted in the ground, the everyday, the animal. The cosmic is carnal.

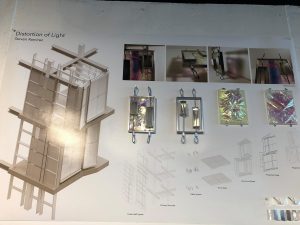

- STEMbending. If Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot invoked the sciences to harden Romantic conceptions of poets and poetry, Loy’s “Songs to Johannes” puts love in the laboratory. Instead of strapping on STEM, these poems shape it to avant-garde poetics. In Poem 14 physical love is pure physics: the impact of lighted bodies / Knocking sparks off each other / In chaos. Generating from the scientific term nucleus, Poem 33 proclaims that Proto-plasm was raving mad / Evolving us. In Poem 23, the stock romantic image of the moon will Bleach / To the pure white / Wickedness of pain. Love is chemical.

- Body Mechanics. When love isn’t animal or chemical, it’s often mechanical in these poems. Loy trafficked in Futurism and Surrealism. Her Aphorisms on Futurism reflects only part of her vexed relationship with F. T. Marinetti. In Poem 13, her pun Where two or three are welded together plays on religious rituals of marriage (welded/wedded) and worship. In Poem 25, the lovers turn into machines in the light of an erotic sunrise (little rosy / tongue of Dawn), staring out with steel eyes.

- Mind the Gaps. Many of Loy’s lines bear rifts, apt gaps reflecting fractured relationships, formal rupture, even atomic fission (Nucleus Nothing). If Gertrude Stein disrupted legibility with syntax, Loy opens fissures and apertures in her poetics. In the opening to Poem 12, Loy breaks down the confines of passion to its fractious elements: Desire Suspicion Man Woman. Deflating romance, Poem 15 breaks up its address to the you:

But you alone

Superhuman apparently

If her foremother Emily Dickinson deployed dashes, Loy forms dashed phalanxes within and between her lines of words. In Poem 28, for example:

Unthinkable that white over there

— — — Is smoke from your house - Aleatoric Form. With “Songs” in the title, music is in play in Loy’s poetic sequence. Poems 1 and 33 function as endpoints, framing a shifting spectrum of discourses on love and passion. The Pig Cupid in Poem 1 uproots allusions to fairy tales (“Once upon a time“) and youthful promiscuity (wild oats). Poem 34 declares Love as the preeminent litterateur. Loy’s sequence reclaims the love poem, revising and remixing it. Aleatoric compositions allow for randomness and improvisation. In “Songs for Joannes,” poems 2-33 can be moving parts. The numbered sequence is not linear. –MB